‘The customers are still there’: Welsh mussel farmers hope post-Brexit reset can revive business

Rising out of the water, nets bulge with thousands of blue mussels.Pulled back to the dredging boat, they are emptied into a hopper and rinsed with water.They have just been harvested fresh from the bottom of the Menai Strait, the channel that separates the north Wales mainland from the island of Anglesey.On a blustery, damp morning, skipper Alan Owen guides the 43-metre Valente out of Port Penrhyn, close to the city of Bangor, towards the mussel grounds around the pier.“It’s windy today but we’re not jumping up and down as there aren’t big waves.

If Anglesey wasn’t there it’d be a different story,” says Owen.“Our geographical position makes this probably the best place in Britain for producing mussels,” he adds, pointing to the boat’s screen, where different colours display the areas where several companies are licensed to harvest the shellfish.“It’s because of the tidal exchange going through the Menai Strait, it gets up to six knots in the middle there,” he says.“You’ve got a massive volume of water exchanging both ways, bringing in the food and nutrients the mussels like.”It was these natural advantages that helped turn the eastern Menai Strait into the largest mussel farming area in Britain from the 1960s onwards, employing scores of local people including Owen’s father and uncle.

Over the years, as production increased, the vast majority of the mussels were sent across the Channel to Europe, where diners – especially in France, Belgium and the Netherlands – tend to eat a lot more shellfish.The UK’s shellfish industry is small and specialised, valued before Brexit at less than £12m a year, but one which is crucial for some coastal communities.Britain’s departure from the EU closed off most access to the lucrative European export market, and has all but ended the industry in the Menai Strait.Since Brexit, mussel production has collapsed from about 10,000 tonnes annually to just five tonnes in 2022, representing just 0.05% of the previous total.

The Valente is the last remaining mussel dredging boat at Port Penrhyn; the other three have been sold off or redeployed.The company which owns the Valente, Myti Mussels is the only one of four mussel fishing companies fully operating.It now just sells small quantities of molluscs to UK customers.There is, however, a glimmer of hope on the horizon in the shape of the “reset” deal between Keir Starmer’s UK government and the EU, announced in May.Britain’s shellfish exporters and other food producers are expected to be one of the main beneficiaries of the UK-EU reset, designed to remove the need for sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) controls at the border, which formed part of post-Brexit trading requirements, along with health and veterinary checks and supplementary paperwork.

The administrative burden was one of the reasons for the collapse in exports from north Wales, resulting from longstanding EU rules concerning imports of shellfish including mussels, oysters, clams, cockles and scallops – collectively known as live bivalve molluscs – from non-EU member states.Molluscs caught outside the EU can only be imported to the bloc without treatment if they come from waters with the highest quality rating, while vessels from non-EU states are also not permitted to land live bivalve molluscs in EU ports.The waters of the Menai Strait are, like the majority of those in England and Wales, rated “class B” for shellfish production, which is assessed according to the levels of E coli detected in shellfish flesh.This means mussels from the area can be sold for human consumption provided they are either purified in an approved location, or moved for at least a month to “class A” water, or alternatively treated with heat.Some fishers believe that sewage outflows into the Menai Strait after heavy rain has not helped improve the water quality in recent times.

Mussels from “class B” waters can still be exported to the EU, provided they are first purified – or depurated in industry parlance – by being placed for a day or two in tanks of clean seawater which has been sterilised using ultraviolet light.This process is costly and can cause stress for the molluscs, reducing their shelf life and making them less attractive to European buyers.There isn’t a purification plant in Bangor, or indeed in the UK, that could handle the volumes of molluscs exported pre-Brexit.However, that should be about to change, as an Irish seafood company has fitted out a building next to Port Penrhyn, which is awaiting certification.This investment and news of the reset talks have given Owen hope that the local industry can be resurrected.

“The customers are still there,” he says.“Where we are situated, weather-wise, we are 100% reliable.If they pick up the phone and order, we deliver.”Sign up to Business TodayGet set for the working day – we'll point you to all the business news and analysis you need every morningafter newsletter promotionOwen’s son Martin followed his father into mussel harvesting, but the state of the industry means he has other ambitions for his grandson, Martin’s 12-year-old son.“We’ve taken him out on the boat a few times and he likes it, but he isn’t yet old enough to decide what he wants to do for a job,” says Owen.

“He has got the brains to go into something better.”Others are less optimistic about the industry’s future prospects.James Wilson is one of the owners of the mussel producer Deepdock.The business has stopped trading since Brexit and Wilson now runs a fish and seafood shop next to the port for part of the week, alongside teaching at Bangor university.“We tried every possible avenue that we could think of to try to secure some stable access to the EU market, but found a locked door at the end of it,” Wilson says, in between wrapping up fish fillets for customers.

He was initially encouraged by news of the reset talks, but given that any implementation of an SPS deal is unlikely to happen before 2027, Wilson worries it will be hard to restart significant mussel exports.The local mussel beds would also need to be repopulated.This requires very young mussels – called seed mussels – to be collected from other naturally occurring beds and laid in licensed areas, where they usually need a couple of years to grow to a marketable size.“There’s always uncertainty, particularly in respect of the juvenile mussels, the seed mussels, so we have natural variability associated with that,” Wilson says.“If you’ve got an input uncertainty with the seed, added to an output uncertainty as to whether you’ll be able to sell anything you’ve got on the ground, it’s just too much.

It’s a big investment, millions of pounds, to buy a boat, run it, crew it.You’ve got to have certainty.”Many other shellfish businesses around the UK are “on hold”, says David Jarrad, the chief executive of the industry body the Shellfish Association of Great Britain.“So much for a reset,” he adds, saying “the longer it takes [to implement an SPS agreement with the EU], the less chance there is that they will be able to start trading again.”He and many others believe the UK is missing out on a potential growth sector, supplying customers with a large appetite for British shellfish.

“The UK is located in the sweet spot for cultivating shellfish almost anywhere in the world,” Jarrad says.“Our aquaculture industry is minuscule in comparison with Spain and France and the Netherlands, even though we have a greater coastline.”A government spokesperson said: “We are focused on negotiating an SPS deal that could add up to £5.1bn a year to our economy, by cutting costs and reducing red tape for British producers and retailers.”Back at the fish shop next to Port Penrhyn, Wilson wonders whether a future SPS agreement could inspire a new generation of mussel fishers.

“Maybe if somebody with a bit more enthusiasm, a bit more energy, a bit of money comes in, then it might all happen.”

How to turn the dregs of a jar of Marmite into a brilliant glaze for roast potatoes – recipe | Waste not

I never peel a roastie, because boiling potatoes with their skins on, then cracking them open, gives you the best of both worlds: fluffy insides and golden, craggy edges. Especially when you finish roasting them in a glaze made with butter (or, even better, saved chicken, pork, beef or goose fat) and the last scrapings from a Marmite jar.I’ve always been fanatical about Marmite, so much so that I refuse to waste a single scoop. I used to wrestle with a butter knife, scraping endlessly at the jar’s sticky bottom, until I learned that there’s a reason the rounded pot has a small flat spot on each side. When you get close to the end of the jar, store the pot on its side, so the last of that black gold inside pools neatly into the side for easy removal

What’s the secret to great chocolate mousse? | Kitchen aide

I always order chocolate mousse in restaurants, but it never turns out quite right when I make it at home. Help! Daniel, by email“Chocolate mousse defies physics,” says Nicola Lamb, author of Sift and the Kitchen Projects newsletter. “It’s got all the flavour of your favourite chocolate, but with an aerated, dissolving texture, which is sort of extraordinary.” The first thing you’ve got to ask yourself, then, is what kind of mousse are you after: “Some people’s dream is rich and dense, while for others it’s light and airy,” Lamb says, which is probably why there are so many ways you can make it.That said, in most cases you’re usually dealing with some form of melted chocolate folded into whipped eggs (whites, yolks or both), followed by lightly whipped cream

The small plates that stole dinner: how snacks conquered Britain’s restaurants

It’s love at first bite for diners. From cheese puffs to tuna eclairs, chefs are putting some of their best ideas on the snack menuElliot’s in east London has many hip credentials: the blond-wood colour scheme, the off-sale natural wine bottles, LCD Soundsystem and David Byrne playing at just the right decibel. The menu also features the right buzzwords, such as “small plates” and “wood grill”.But first comes “snacks”. There are classics: focaccia, olives, anchovies on toast

‘Alicante cuisine epitomises the Mediterranean’: a gastronomic journey in south-east Spain

The Alicante region is renowned for its rice and seafood dishes. Less well known is that its restaurant scene has a wealth of talented female chefs, a rarity in SpainI’m on a quest in buzzy, beachy Alicante on the Costa Blanca to investigate the rice dishes the Valencian province is famed for, as well as explore the vast palm grove of nearby Elche. I start with a pilgrimage to a restaurant featured in my book on tapas, New Tapas, a mere 25 years ago. Mesón de Labradores in the pedestrianised old town is now engulfed by Italian eateries (so more pizza and pasta than paella) but it remains a comforting outpost of tradition and honest food.Here I catch up with Timothy Denny, a British chef who relocated to Spain, gained an alicantina girlfriend and became a master of dishes from the region

Rukmini Iyer’s quick and easy recipe for spiced paneer puffs with quick-pickled carrot raita | Quick and easy

These moreish little pastries are as lovely for a snack as they are for dinner, and they take just minutes to put together. I like to fill squares of pastry and fold them into little triangular puffs, but if you prefer more of a Cornish pasty look (*food writer cancelled for suggesting paneer is an appropriate pasty filling!*), by all means stamp out circles, fold into half-moons and crimp the edges.Prep 20 min Cook 25 min Serves 3-4225g block paneer 2 spring onions, trimmed20g mint leavesZest of 1 lime, plus 15ml lime juice1 green chilli, deseeded if you wish1 heaped tsp flaky sea salt1 tbsp self-raising flour320g roll puff pastry 1 egg, beatenFor the quick-pickled carrot raita ½ tsp fennel seeds ½ tsp coriander seeds, lightly crushed30ml white-wine vinegar½ tsp flaky sea salt, crumbled2 spring onions, trimmed and finely chopped300g carrots, peeled, quartered lengthways and finely sliced150g natural yoghurtHeat the oven to 220C (200C fan)/425F/gas 7. Tip the paneer, spring onions, mint leaves, lime zest and juice, green chilli and salt into a food processor, and blitz, scraping down the sides occasionally, until the mix resembles very fine couscous. Add the flour, and blitz again until the mix has broken down even more finely

Chef Skye Gyngell, who pioneered the slow food movement, dies aged 62

Tributes have been paid to the pioneering chef and restaurant proprietor Skye Gyngell, who has died aged 62.The Australian was an early celebrity proponent of using local and seasonal ingredients and built a garden restaurant from scratch, the Petersham Nurseries Cafe in Richmond, south-west London, which went on to win a Michelin star.A statement released by her family and friends read: “We are deeply saddened to share news of Skye Gyngell’s passing on 22 November in London, surrounded by her family and loved ones.“Skye was a culinary visionary who influenced generations of chefs and growers globally to think about food and its connection to the land.“She leaves behind a remarkable legacy and is an inspiration to us all

Soup firm Campbell’s dismisses executive over alleged ‘poor people’ comments

‘The customers are still there’: Welsh mussel farmers hope post-Brexit reset can revive business

European parliament calls for social media ban on under-16s

ChatGPT firm blames boy’s suicide on ‘misuse’ of its technology

Geraint Thomas lands new Ineos role as struggling team make major reshuffle

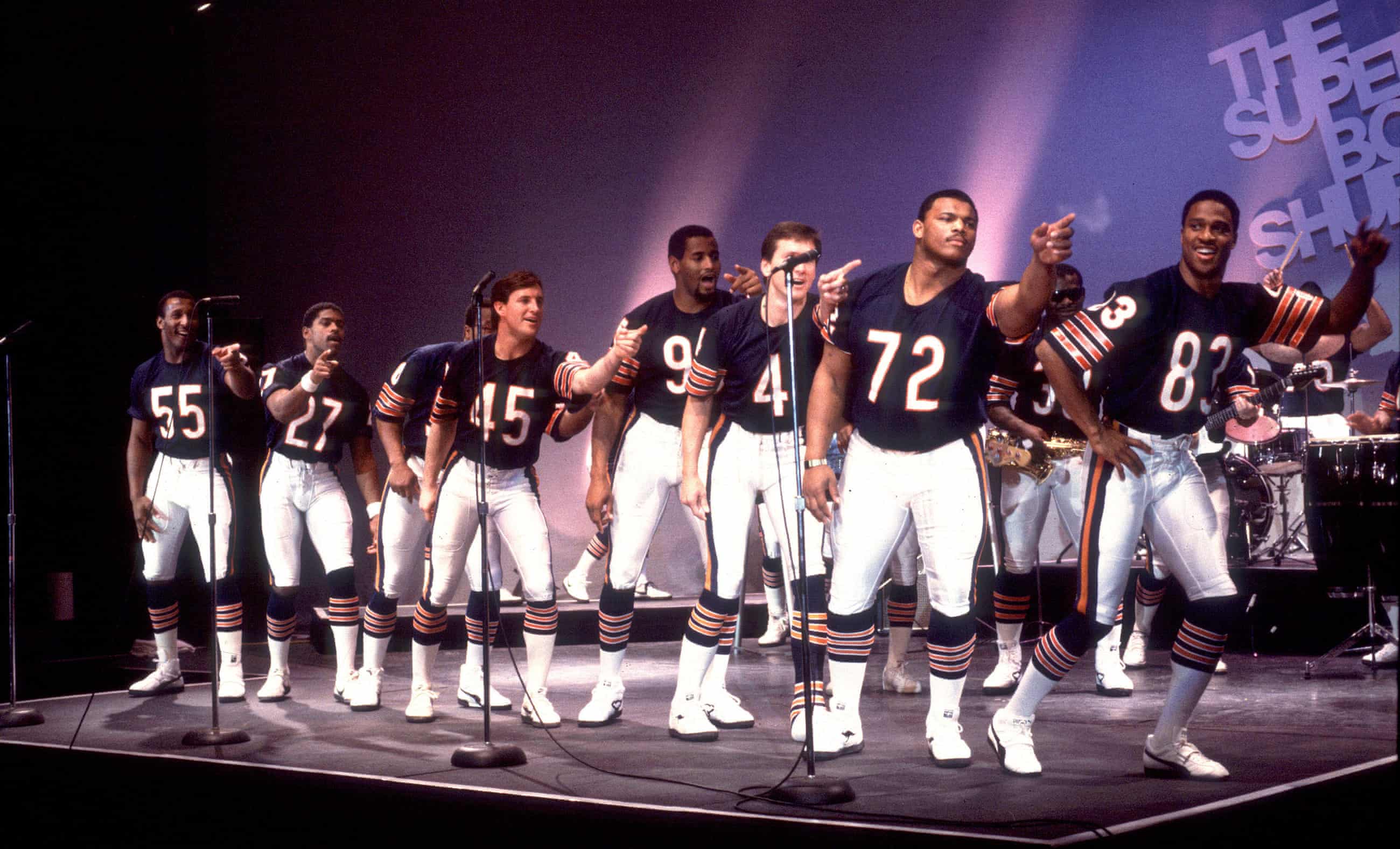

The Super Bowl Shuffle at 40: how a goofy rap classic boosted the Bears’ title run