The Spin | Ricky Ponting’s prescient call and the joy of being a cricket soothsayer

Have you ever accurately predicted what will happen on a cricket pitch before the ball has been bowled? It’s an incredible feeling.That moment when you glance at the field, remember who’s on strike and think: “Here comes the short ball,” only for it to arrive, be pulled and then safely pouched by the fielder you had mentally circled at deep square.For a split second you feel omniscient.Like you’ve cracked the code.Cricket, more than any other sport, invites this kind of clairvoyance.

Its patterns are legible, its traps visible, its repetitions comforting.Even the greats get a kick out of playing soothsayer.During the third Test of the recent Ashes, Ricky Ponting was calling the action for Channel 7 when Pat Cummins was at the crease getting ready to face Brydon Carse.“We saw Cummins last over get unsettled by one that angled back up into the left armpit,” Ponting said.“He’s not a great ducker of the ball, he tries to ride the bounce and that’s why I like this field.

You got one back on the hook so you can’t play that, you got one waiting under the helmet at short leg.”Like clockwork, Australia’s captain clipped a bouncer straight to Ollie Pope at short leg.Ponting, a man who achieved everything in the sport, leaned back with a self-satisfied smile.Social media did the rest: clips, plaudits, gifs, the familiar chorus about his genius and uncanny ability to see the game three balls ahead.But there was a quieter truth sitting in plain sight.

Ponting hadn’t set the ambush,Ben Stokes had,The field was already in place, the short ball already part of the plan,Ponting’s gift wasn’t prophecy so much as pattern recognition, an elite understanding of why a decision had been made, not ownership of the decision itself,That distinction matters.

Because modern cricket is increasingly a game of premeditated choices: tendencies logged and weaknesses stress-tested before the bowler starts his run-up,What looks like instinct is often preparation made invisible,We applaud the voice that calls it, not the hand that sets it, and, in doing so, we miss the more interesting story, about how captaincy now lives somewhere between gut feel and hard data,To understand why moments such as Ponting’s feel so prophetic, it helps to understand the architecture beneath them,In modern cricket, foresight increasingly has a name: the matchup.

Ben Jones, a senior analyst with CricViz who has worked with franchise teams around the world, defines it simply.“A matchup is a good option to bowl to a certain batter, or a good option for a batter to face a certain bowler.” At heart, it’s about engineering advantage.“You’re trying to create a situation where a well-suited player from your side is up against a poorly suited player from the other side.”The idea itself isn’t new.

“Captains have always thought about who is a good bowler to bowl to this batter,” Jones says.“What’s changed is how you arrive at those matchups and how they are communicated.”Where once this was intuition and experience, it is now increasingly the output of databases and models.Analysts can examine head-to-head history, release heights, speeds and swing types.That influence is no longer discreet.

“The analyst used to be the nerd in the back of the box,” Jones says.Now analysts sit on auction tables, relay signals from dressing rooms and shape decisions in real time.“There’s a greater acceptance of data from players who’ve grown up in franchise cricket.”Jones is quick to stress its limits.He recalls pushing hard for Phil Salt and Will Jacks to open for the Pretoria Capitals in the SA20, arguing Kusal Mendis’s numbers against pace and bounce made him a poor option.

The head coach, Graham Ford, overruled him and Mendis, having worked on this weakness, tore the tournament apart.That anecdote resonates with Adam Hollioake, the former England and Surrey captain who won three County Championships between 1999 and 2003, just before the data revolution.For him, the danger lies not in information itself, but in mistaking it for truth.“It’s a good servant, but a bad master,” Hollioake says.He offers himself as an example.

“You could look at the numbers and say I wasn’t very good against leg-spin because I got out to Shane Warne,” he says.“But if someone bowled poor leg-spin at me, I was very good at destroying it.Data can lie.You’ve got to be careful when you take it as gospel.”Hollioake remembers captaincy as a craft built on conversation and memory rather than metrics.

“It was about asking people their experience, drawing out information, and then the captain remembering and applying it at the right time.” In his view, the game has come full circle.“Pre-1995, applied cricket knowledge was the be-all and end-all.Then analysis came in and whoever had it had a competitive advantage.Now everyone’s got an analyst.

So the advantage comes back to who can apply the information best.”Which is why moments such as Ponting’s resonate so strongly.They feel like prophecy, but they’re really recognition: the ability to read patterns, remember past events and understand why a field has been set.We may still applaud the voice that calls it, but the game itself is reminding us that insight has always been shared between numbers and nerves, between preparation and feel.Still, when it clicks, there’s no better feeling.

This is an extract from the Guardian’s weekly cricket email, The Spin.To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions

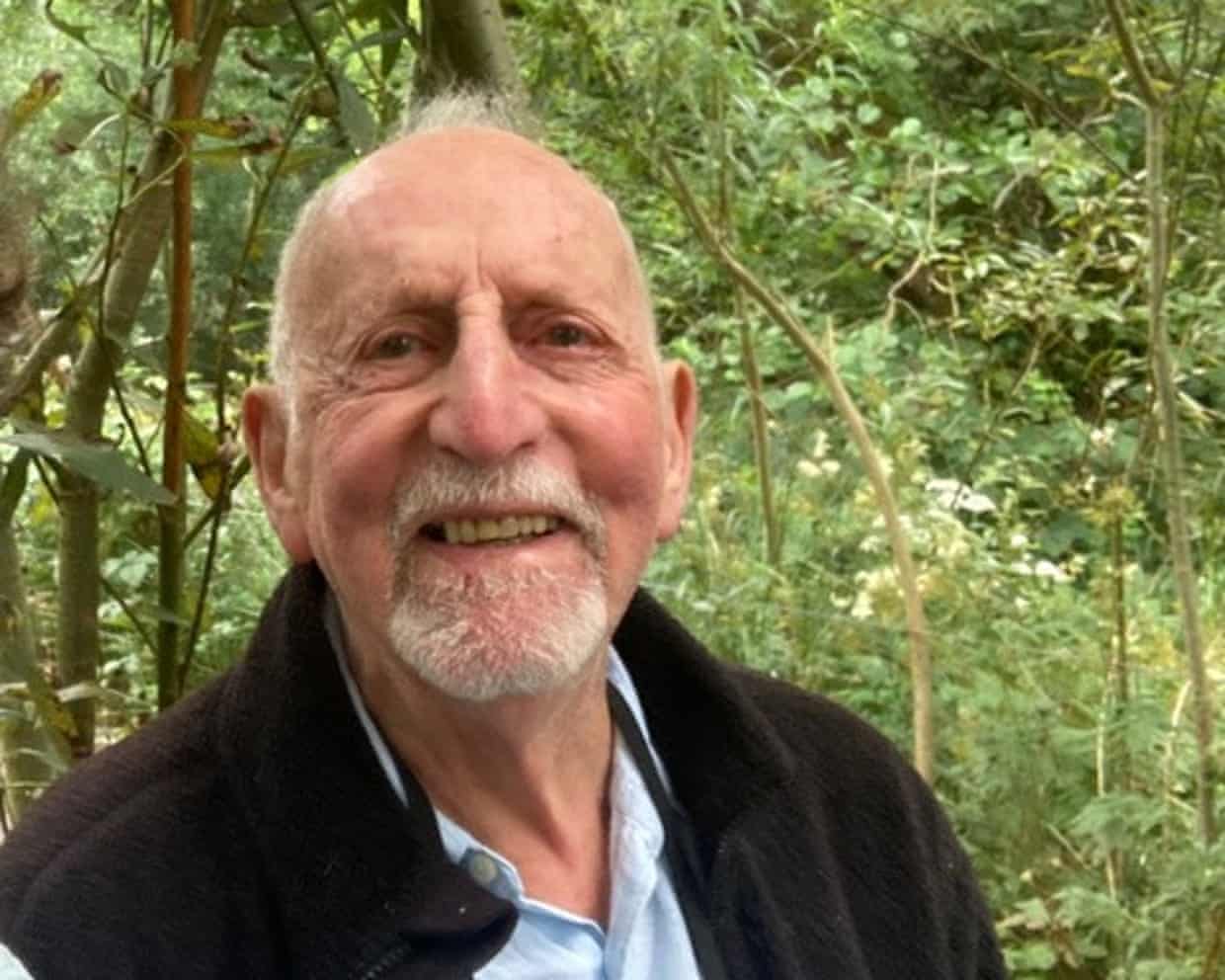

Michael Baron obituary

The London solicitor Michael Baron, who has died aged 96, was instrumental in changing the lives of autistic people for the better. At a time when autism was little known or understood, in 1962 he co-founded the UK’s leading autistic charity. As its first chair, he was the driving force in publicising the condition and raising funds.He helped set up the world’s first autism-specific school in 1965 and the first residential community for autistic adults in 1974. As one of a group of lawyers, he campaigned for the Education (Handicapped Children) Act in 1970, which gave all children, regardless of disability, the right to an education

Educational background key indicator of immigration views in UK, study finds

Rightwing movements are struggling to gain support among graduates as education emerges as the most important dividing line in British attitudes towards politics, diversity and immigration, research has found.A study from the independent National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) found people with qualifications below A-level were more than twice as likely to support rightwing parties compared with those with qualifications above.The Demographic Divides report says: “A person with no educational qualifications had around 2 times the odds of voting for either the Conservatives or Reform UK than someone with a university degree or higher. This is independent of other factors, including financial precarity, so those without a degree are more likely to support rightwing parties in the UK even after adjusting for their financial situation.“If one wanted to predict whether a person voted for parties of the right in the UK, knowing their educational background would give them a very good chance of making a correct prediction

Prostate cancer is most commonly diagnosed cancer across UK, study finds

Prostate cancer is now the most commonly diagnosed form of cancer across the UK, surpassing breast cancer, according to a leading charity.There were 64,425 diagnoses of prostate cancer in 2022, an analysis of NHS figures by Prostate Cancer UK found, and 61,640 new cases of breast cancer.The analysis found there to be a discrepancy at which stage men with prostate cancer were diagnosed, with 31% of men in Scotland diagnosed with prostate cancer at stage 4, compared with 21% of men in England.About one in eight men across the UK will be affected by prostate cancer in their lifetimes, with approximately 12,200 deaths each year caused by the disease.One in four black men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetimes

Don’t rely on BMI alone when diagnosing eating disorders in children, says NHS England

A child’s body mass index should not be the key factor when deciding which under-18s get help for an eating disorder, the NHS has told health professionals.The new guidance from NHS England to GPs and nurses follows criticism that over-reliance on BMI has led to children who have an illness such as anorexia or bulimia being misdiagnosed and missing out on care.“Single measures such as BMI centiles should not be a barrier to children and young people accessing early and/or preventative care and support,” it says.Other factors, such as changes in behaviour by the young person and concerns raised by their family, should help guide decision-making, according to the document. It was welcomed by Beat, an eating disorders charity, and the Royal College of Psychiatrists, both of which helped draw it up

The inside track on curbing UK prison violence | Letters

Alex South’s harrowing account of violence in prisons (Death on the inside: as a prison officer, I saw how the system perpetuates violence, 13 January) deserves more than our sympathy – it demands we recognise these murders and assaults not as symptoms of a broken system, but as a foghorn blaring warnings about fundamental failures.I work in prisoner rehabilitation. I see what South describes from the other side: men whose “scaffolding” is indeed flimsy, who have accumulated trauma before and during incarceration. But I also see what happens when that changes. Our service users work in cafes, bakeries and bike shops, not because we believe in the redemptive power of bread or bicycles, but because meaningful work and purposeful activity are the foundations of desistance

She’s just autistic Barbie – let children play | Letters

As the parent/carer of autistic children, I’m pleased that my kids have more visibility in mainstream culture with the launch of the “autistic Barbie” doll (Mattel launches its first autistic Barbie, 12 January). For the kids, they’re interested, but, given my youngest’s penchant for graffiti, “autistic Barbie” will be drawn all over and resemble “weird Barbie” in no time.I’ve found it hard to share this pleasure, having seen my academic and activist colleagues slam the doll. I completely understand their reasoning. Of course it lacks nuance to use visible accessories to represent a hidden disability

The Guide #226: SPOILER ALERT! It’s never been easier to avoid having your favourite show ruined

From 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple to A$AP Rocky: your complete entertainment guide to the week ahead

Jimmy Kimmel on the midterms: ‘We can’t have an election soon enough’

Civilised but casual, often hilarious, Adelaide writers’ week is everything a festival should be – except this year | Tory Shepherd

‘Soon I will die. And I will go with a great orgasm’: the last rites of Alejandro Jodorowsky

Call this social cohesion? The war of words that laid waste to the 2026 Adelaide writers’ festival