The hidden victims of the opioid crisis: the ones who lived

John-Bryan “JB” Jarrett was supposed to be fishing on the Saturday morning of Labor Day weekend, September 2020.Over dinner the night before, he told his mom, Jessica, he wanted to be on the water by 7am.Jessica and JB were unusually close.When her work brought her to Austin, she stayed in his spare room; when the pandemic hit, she moved in for good.Despite a full life – a girlfriend, a job, a side hustle running an online thrift store – he welcomed her.

They planted vegetables, packed meals for homeless people, watched true crime, even shared their phone locations.That morning, Jessica woke up eager to text him the same silly joke she always sent on his fishing trips: a screenshot of his coordinates – a dot in the water – captioned: “YOU’RE IN THE MIDDLE OF THE RIVER!”But JB’s phone did not show up on the map.It was off.Jessica started calling his friends, all of whom had lost track of him the previous night.Then she received a message on Instagram: “URGENT,” it said, next to a phone number.

“Call now.”JB had overdosed on fentanyl and had been found unresponsive in a friend’s apartment.No one knew how long he had been without sufficient oxygen.He was transported to an Austin-area hospital, where the damage became clear: JB had sustained a brain injury and severe damage to his liver and kidneys.By the standard measures of America’s opioid crisis, JB was one of the lucky ones.

He did not get added to the nation’s tally of overdose opioids deaths – an estimated 55,000 in 2024, and more than 1m over the past 20 years.But having survived, the 30-year-old now lives with life-changing injuries.Five years on, JB cannot walk or talk.After some recent medical setbacks, he also struggles to move, swallow or communicate in any way.Jessica now provides him near round-the-clock care.

She sleeps in his bedroom closet, her makeshift bed wedged between the wall and a rack of clothes, to be close enough to respond to every cry, call, shift of bedsheet, or other sign that JB is in distress.During the day, she works remotely as a social media manager and does her best to keep him engaged and comfortable.JB’s story highlights a cruel irony: while overdose deaths have declined, thanks in part to the life-saving drug naloxone (better known by the brand name Narcan), more people are surviving with serious, sometimes devastating complications.This is the epidemic within the epidemic – one we rarely count.I knew JB’s story was not unique: my family had lived through something similar.

My cousin’s only son, Mason Bogert, overdosed on synthetic opioids and benzodiazepines when he was 18.He was a shy, kind, gifted kid who loved cats, guacamole and pulling a good prank.He was so adept with computers that he developed a popular weather app at age 16.But he also struggled with anxiety and depression, and self-medicated.His tech skills became an accomplice to addiction: he used the dark web to buy the drugs that almost killed him, selected because they could evade detection in urine tests.

His parents found him without a pulse on Mother’s Day morning, 2016.He lived the next five years in need of constant care, shuffling between ICUs, rehabilitation hospitals and nursing homes across New England.The overdose left him blind and immobilized by spasticity, or very stiff muscles, a condition common with severe brain injury.But, over time, Mason became increasingly aware.He began to communicate by spelling – opening his mouth to signal the correct letter – a method that allowed greater self-expression, and revealed he understood his circumstances and that he was deeply sad and frustrated by them.

Four years into his ordeal, we gathered to celebrate the fact that the earnings from his app had just broken the million-dollar mark – symbolic of a promising, even brilliant young life cut short.He died from pneumonia a few months later, two days after his 23rd birthday.No one knows how many people survive opioid overdoses.The CDC’s best estimate is that for every fatal overdose, there are 15 non-fatal ones – which puts their number at well over 1m annually in recent years.Dr Nora Volkow, the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, shared with me her “conservative” but staggering estimate that half a million Americans each year risk brain damage from opioid-induced hypoxia, which is when the body is not receiving an adequate amount of oxygen.

What effect these events have on people’s health, and how many are truly affected are burning questions.Volkow believes most injuries manifest in quiet but life-altering ways such as memory loss or diminished executive function.They can affect one’s ability to hold down a job, or fully participate in addiction recovery.Severe cases can drain patients of their life potential, according to Dr Jennifer Stevens, the director of the Center for Healthcare Delivery Science at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.Young people in particular can become “incredibly financially toxic to themselves and their loved ones” when they are not able to work or require long-term support.

In other words, surviving an overdose can leave families fighting a different kind of crisis – one measured not in deaths, but in years of care,An overdose occurs when opioids overwhelm receptors in the brain, leading to slower breathing and respiratory depression,Experts believe brain injuries can occur after four or five minutes of inadequate respiration,The longer the brain and body go without sufficient oxygen, the worse injuries are likely to be – but outcomes remain a bit of a black box,A few years ago, Ashley Six-Workman, a nurse with West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, found a woman who had overdosed and been down for at least a few minutes in a parking lot.

She did not have Narcan, so when she began doing CPR and waiting for emergency medical services, she feared the worst: she thought she was going to have an anoxic brain injury.When the woman walked out of the hospital three days later, Six-Workman was both relieved and intrigued.“Clinically, in my head, it didn’t make sense,” she told me.“She should have some sort of impairment.”Data from a rare study of overdose-related ICU admissions from 162 hospitals between 2009 and 2015 offers a sense of scale of the most extreme cases: of the 21,705 patients who required critical care, 8% suffered a catastrophic anoxic brain injury.

But this data predates the opioid epidemic’s “third wave”, when fentanyl drove overdoses to unprecedented levels – so today’s numbers are almost certainly higher.Because fentanyl crosses the blood-brain barrier so easily, it can trigger an overdose within minutes, leading to respiratory depression and cardiac arrest.“You have a faster onset and a narrower window to intervene,” said Erin Winstanley, a professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.At the same time, naloxone has saved millions of lives: pharmacies sold 12.9m doses between October 2002 and September 2023.

Yet each revived overdose also means another survivor left at risk of lasting complications.It is also increasingly common for people to live through not just one, but multiple overdoses.Jon Zibbell, an epidemiologist who studies adverse health outcomes among people who inject and smoke street drugs, became concerned about the phenomenon as he witnessed people repeatedly overdosing on fentanyl and being revived by Narcan.That survival is, on its face, a triumph of advocacy and harm-reduction policy.But Zibbell now worries about the cumulative toll.

People he knew often felt “off-kilter” after a single overdose; what happens after a series of them?He hypothesizes that the repeated injuries may be somewhat analogous to what happens with a cluster of mini-strokes – or to football players who, after multiple minor concussions, develop chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a devastating neurodegenerative disease.But it is going unnoticed, he adds, because non-fatal overdoses are perceived as harmless, and because their effects are often not obvious.He and his co-authors flagged the issue in a federal report on the health consequences of non-fatal overdoses back in 2019.“I believe it’s a silent epidemic of many non-fatal overdoses,” he told me.Early research supports this theory, and suggests repeated non-fatal overdoses may lead to Alzheimer’s-like brain pathologies.

Postmortem studies show elevated tau levels, the protein found at high levels in Alzheimer’s and CTE patients, while imaging of survivors reveals reduced hippocampal volume.The problem has only grown more urgent as the drug supply has become increasingly toxic and unpredictable, said Zibbell.Today, Americans are not exposed to fentanyl alone, but instead are consuming a cocktail of lesser-known synthetic substances, and these contaminants can limit the effectiveness of Narcan and prolong downtimes.Recent CDC data appears to reflect his concern: between 2021 and 2023, ER visits for opioid overdoses declined, but related hospitalizations rose – suggesting patients now arrive in more serious condition.For Zibbell, it marks a new phase in the opioid crisis: one that may be less likely to kill, but more likely to harm.

Almost from the moment Jessica arrived at the hospital after JB’s overdose, she sensed she and his medical team were on opposing sides.She was waiting for JB to wake up, she said, while they were waiting for JB to die.Jessica remembers doctors aggressively urging them to withdraw life support on the second day of his hospitalization.“We were being literally harassed for his organs,” she said.Compared with traumatic brain injuries, anoxic and hypoxic injuries caused by oxygen deficiency are barely studied, in part because outcomes have generally been considered very poor.

(One neurologist, who wants to remain anonymous, told me that when his friend’s heart attack resulted in such an injury, his first impulse was “to put a pillow over his head”; that friend has fully recovered and remains alive decades later.)When JB first opened his eyes five days in, the neurologist refused to watch Jessica’s video proof of it; it would not change his recommendation, he told her.JB then moved to a long-term acute care facility that specialized in neuro-rehabilitation.It should have been an ideal place for him, but he languished there, heavily medicated and unable to actively “participate” – as required by insurance companies – in therapy.As a result, staff withheld those activities, including the stretching of limbs.

Four months after his overdose, JB still had not been out of a hospital bed.At one point, he dislocated his hip, an excruciating injury that went unnoticed until Jessica pinpointed its source through the rudimentary communication system she had worked out: he would stick out his tongue to signal “yes”, which he did when she pointed to his hip.(The medical staff was skeptical, but a scan indeed showed it was dislocated.)The facility transferred JB to a hospital for care, but because of his condition, no surgeon would operate on him.It was at this point, over the Christmas holidays, that JB and Jessica experienced a sort of miracle.

Through a series of increasingly desperate phone calls, she connected with a doctor who had trained at the Texas Institute for Rehabilitation and Recovery, better known as TIRR Memorial Hermann, one of the nation’s premier brain rehabilitation centers.The Houston-based hospital has a reputation for accepting patients with the most severe injuries and treating them as people with futures and potential.On JB’s first day there, his physical therapist FaceTimed Jessica from the hospital’s outdoor courtyard.She had JB dressed in his own gym clothes, sitting in a wheelchair – a scene that had been unimaginable to her a day before.“That was just like everything, our whole world opening to possibilities,” she recalled.

Over the next three and a half months, as JB received three hours of physical, occupational and speech rehabilitation a day, he showed gradual signs of improvement.He smiled and reacted, gave thumbs ups, and even started to work on communicating with a laser-pointing headband and a letter board.When he was discharged, his injuries were still profound, but each small sign of recovery validated Jessica: JB had already proven the doctors who predicted a permanent vegetative state wrong.A half-dozen families I interviewed described the same experience: once hospitalized with overdose-related brain injuries, their loved ones were treated as lost causes.Many felt judged harshly by medical staff for the role drugs played in the injuries, or for the decisions they made around their care.

And a number shared the belief that young anoxic brain injury patients, often overdose survivors, are prematurely targeted for organ donation,Put simply, trust is low, strained further by the complexity of these cases and the uncertainty among providers about how to treat them,The families I spoke with often trusted the collective wisdom and lived experience of other caregivers online more than doctors, who see these cases rarely and usually not for long,Dr Cindy Ivanhoe, a brain injury specialist at TIRR who treats JB, does not blame them,“It’s a very hard system to navigate,” she said.

“It’s very hard to advocate.” She also sometimes wonders how much of her patients’ complications stem from the side-effects of medications or medical care.The experience can be isolating, too.Several parents told me they were shunned from support groups for families of opioid victims since their loved ones were still alive.Kyle Harman was hooked up to a tangle of machines when his family reached the hospital.

He had overdosed on what the doctors called a “scrambler” – a cocktail of benzodiazepines, opiates and cocaine – and been found by paramedics after an unknown period of time.Harman, then 24, was not breathing on his own, and an EEG showed little brain activity.A restless, thrill-seeking kid who gravitated towards risky sports, Kyle had been battling addiction for years before the overdose that nearly killed him in 2016.He had begun experimenting with drugs in high school, and the following years had been a blur of stress and rock-bottom moments for the whole family.Kyle estimates he overdosed 16 to 18 times, including once when his grandmother had to break the door down.

At the hospital, doctors did not expect Kyle to advance beyond a vegetative state.One offered frank advice: “Consider quality of life over quantity.”Kyle’s parents decided to wait, and in the following days they glimpsed flickers of consciousness.The neurologist cautioned Kyle’s path would not be linear as his body detoxed, neuro-stormed and battled multiple related complications including kidney failure, pneumonia and withdrawal.And it was true: some days, his mother, Lauren, could see signs of her son

Money, muscles and anxiety: why the manosphere clicked with young men – a visual deep dive

Tap to continueClick to continueor use your arrow keysClick Tap here to continueYou are on slide 1 of chapter 1. Use right arrow to continue. Alternatively, use the open square bracket key and close square bracket key to navigate, and disable left arrow and right arrow key navigation. You are on slide 2 of chapter 1. Use right arrow to continue

Garmin Fenix 8 Pro review: built-in LTE and satellite for phone-free messaging

The latest update to Garmin’s class-leading Fenix adventure watch adds something that could save your life: phone-free communications and emergency messaging on 4G or via satellite.The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.The Fenix 8 Pro takes the already fantastic Fenix 8 and adds in the new cellular tech, plus the option of a cutting-edge microLED screen in a special edition of the watch

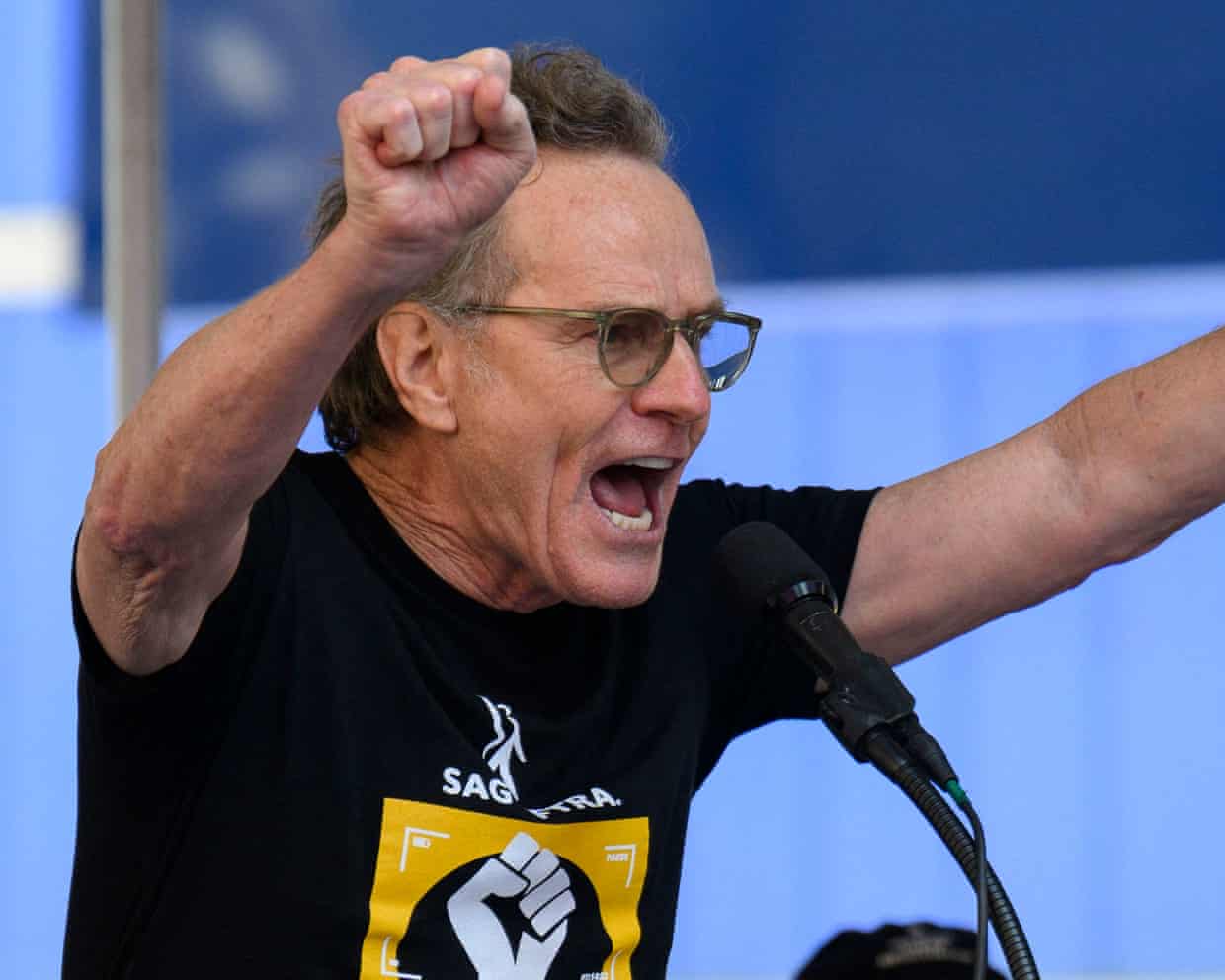

Bryan Cranston thanks OpenAI for cracking down on Sora 2 deepfakes

Bryan Cranston has said he is “grateful” to OpenAI for cracking down on deepfakes of himself on the company’s generative AI video platform Sora 2, after users were able to generate his voice and likeness without his consent.The Breaking Bad star approached the actors’ union Sag-Aftra with his concerns after Sora 2 users were able to generate his likeness during the video app’s recent launch phase. On 11 October, the LA Times described a Sora 2 video in which “a synthetic Michael Jackson takes a selfie video with an image of Breaking Bad star Bryan Cranston”.Living people must ostensibly give their consent, or opt in, to feature on Sora 2, with OpenAI stating since launch that it takes “measures to block depictions of public figures” and that it has “guardrails intended to ensure that your audio and image likeness are used with your consent”.But when Sora 2 launched, several publications including the Wall Street Journal, the Hollywood Reporter and the LA Times reported widespread anger in Hollywood after OpenAI allegedly told multiple talent agencies and studios that if they didn’t want their clients or copyrighted material replicated on Sora 2, they would have to opt out – rather than opt in

‘I’m having a great day’: AWS outage offers some a brief glimpse of a tech-free existence

Workers were sent home, exams were delayed, coffee machines had to be turned on manually and language app users feared their hard-won progress was lost as a result of the global outage of Amazon Web Services on Monday, as some made light of their briefly tech-free existence.A glitch in the AWS cloud computing service brought down apps and websites for millions of users around the world affecting more than 2,000 companies, including Snapchat, Roblox, Signal and language app Duolingo as well as a host of Amazon-owned operations.Many of the sites were restored after a few hours, but some experienced persistent problems throughout the day. By Monday evening, Amazon said all of its cloud services had “returned to normal operations”.But amid the chaos affecting vital services around the world, some more unexpected consequences arose

Amazon Web Services outage shows internet users ‘at mercy’ of too few providers, experts say

Experts have warned of the perils of relying on a small number of companies for operating the global internet after a glitch at Amazon’s cloud computing service brought down apps and websites around the world.The affected platforms included Snapchat, Roblox, Signal and Duolingo as well as a host of Amazon-owned operations including its main retail site and the Ring doorbell company.More than 2,000 companies worldwide have been affected, according to Downdetector, a site that monitors internet outages, with 8.1m reports of problems from users including 1.9m reports in the US, 1m in the UK and 418,000 in Australia

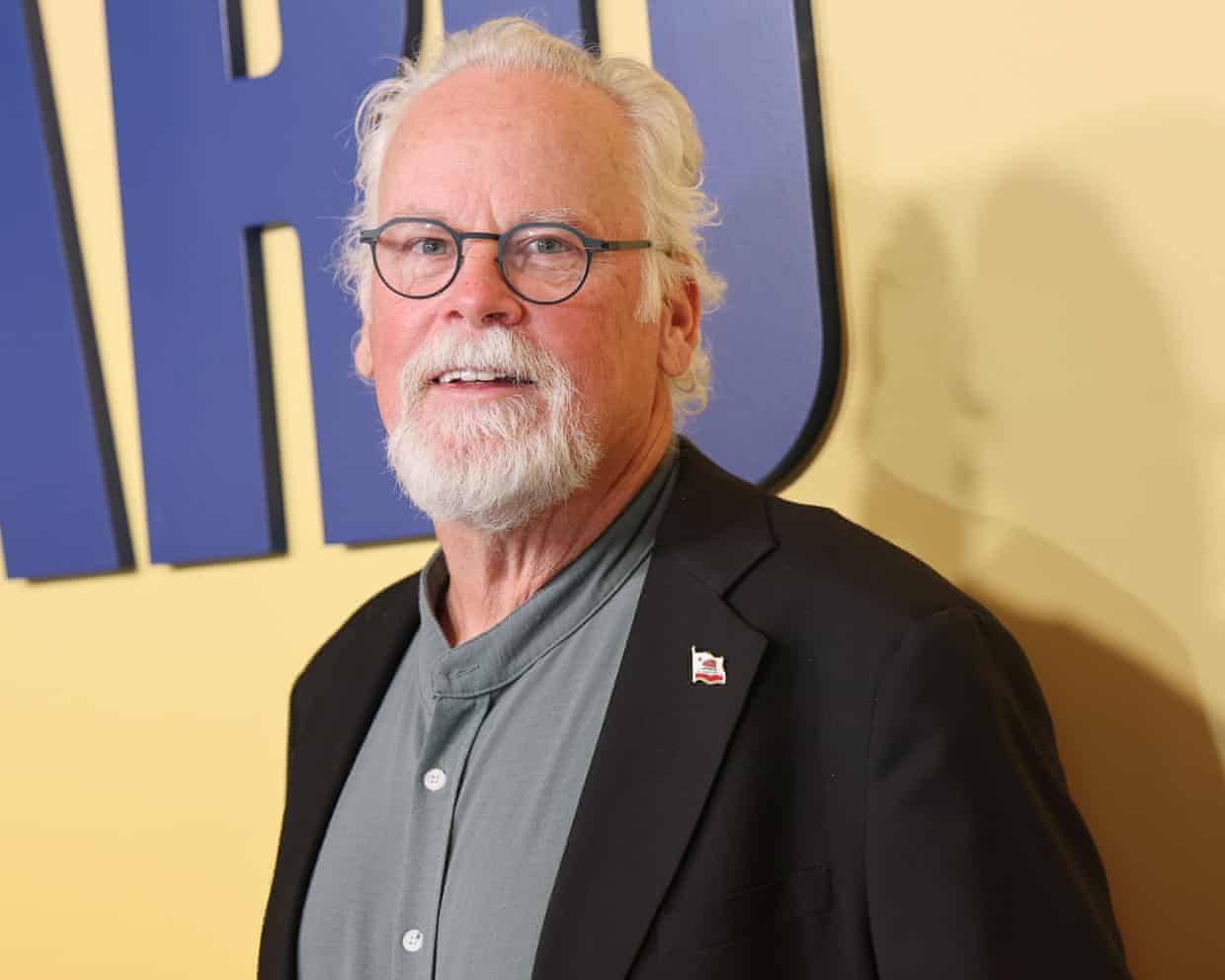

‘Every kind of creative discipline is in danger’: Lincoln Lawyer author on the dangers of AI

He is one of the most prolific writers in publishing, averaging more than a novel a year. But even Michael Connelly, the author of the bestselling Lincoln Lawyer series, feared he might fall behind when writing about AI.Connelly’s eighth novel in the series, to be released on Tuesday, centres on a lawsuit against an AI company whose chatbot told a 16-year-old boy that it was OK for him to kill his ex-girlfriend for being unfaithful.But as he was writing, he witnessed the technology altering the way the world worked so rapidly that he feared his plot might become out of date.“You don’t have to lick your finger and hold it up to the wind to know that AI is a massive change that’s coming to science, culture, medicine, everything,” he said

Scottish hospitality coalition urges chancellor to protect whisky industry

‘I felt my soul leave my body’: 13 readers on the worst meal they ever cooked – from ‘ethanol risotto’ to gravy cake

670 Grams, Birmingham B9: ‘A cascade of small, meaningful bowls that just ooze flavour’ – restaurant review | Grace Dent on restaurants

‘£30 for a ready meal?!’ Do Charlie Bigham’s new dishes really beat going to a restaurant?

‘It’s about weaponising opinion’: the power of Topjaw’s online foodie show

Benjamina Ebuehi’s recipe for peanut butter banana french toast | The sweet spot