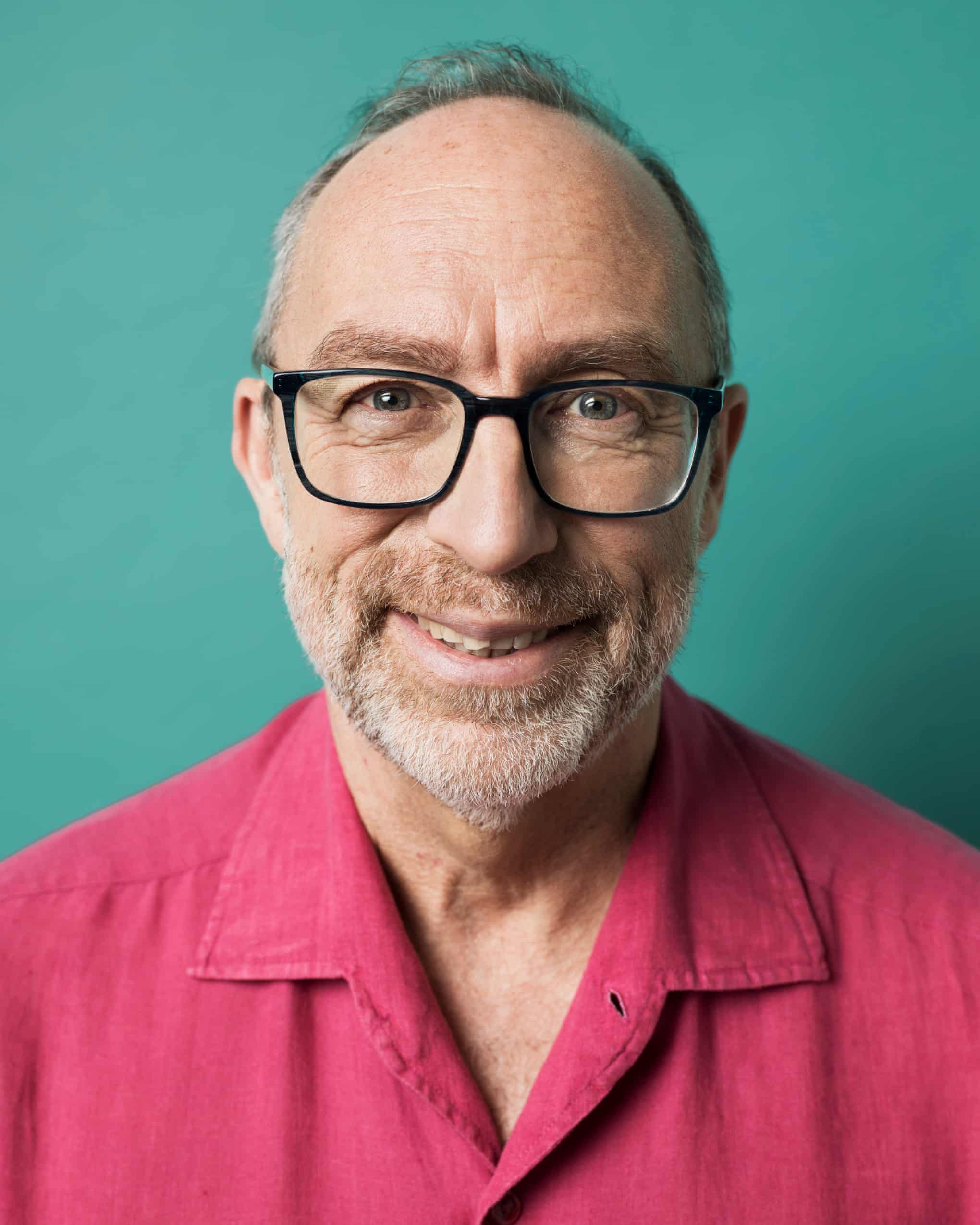

‘People thought I was a communist doing this as a non-profit’: is Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales the last decent tech baron?

In an online landscape characterised by doom and division, the people’s encyclopedia stands out – a huge collective endeavour giving everyone free access to the sum of human knowledge.But with Elon Musk branding it ‘Wokipedia’ and AI looming large, can it survive?Wikipedia will be 25 years old in January.Jimmy Wales’s daughter will be 25 and three weeks.It’s not a coincidence: on Boxing Day 2000 Wales’s then wife, Christine, gave birth to a baby girl, but it quickly became clear that something wasn’t right.She had breathed in contaminated amniotic fluid, resulting in a life-threatening condition called meconium aspiration syndrome.

An experimental treatment was available at the hospital near where they lived in San Diego.Did they want to try it?At the time, Wales was a former trader and internet entrepreneur in his mid-30s.He had co-founded a “guy-oriented search engine” called Bomis, but his real passion was encyclopedias.The money from Bomis had allowed him to found Nupedia, a free online encyclopedia written by experts – but it was proving slow to get off the ground.The laborious process of peer review meant that it only managed to generate 21 articles in its first year (among them “Donegal fiddle tradition” and “polymerase chain reaction”).

Suddenly, Wales needed information, and fast.But as he searched for “meconium” on the wider web, desperate to make a better-informed decision about his daughter’s health, all he found was a mixture of first-hand accounts from strangers he had no way of evaluating and highly technical scientific papers he couldn’t understand.“It was like sifting through the debris of a bombed-out library,” he remembers.Ultimately, he and his then wife decided to trust the doctors and go with the new treatment.Their baby, Kira, pulled through.

But that terrifying scramble made up his mind: Nupedia was never going to work – it was time for a different approach.We know the rest of the story: his new project, Wikipedia, founded on the principle that anyone could edit it, grew rapidly.By 2002, there were about 25,000 entries in the English version; by 2006, there were 1m.There are now more than 7m (the digital version of Encyclopedia Britannica has 100,000).Alongside this are 18 foreign-language versions of Wikipedia that have more than 1m articles each, ranging from Arabic to Vietnamese.

It has become part of the plumbing of the internet – perhaps even more essential: Diane von Fürstenberg once told Wales that “we all use Wikipedia more often than we pee”.In an online landscape characterised by doom and division, it stands out: a huge, collective endeavour based on voluntarism and cooperation, with an underlying vision that’s unapologetically utopian – to build “a world where every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum of all human knowledge”.It has weathered teething troubles (such as a “joke” edit that suggested a loyal aide to Robert F Kennedy was in fact involved in his and his brother’s assassinations) to become a place in which civility and neutrality are the guiding stars, and levels of accuracy match those of academic textbooks.Wales’s new book, The Seven Rules of Trust, is an attempt to distil the secrets of its success.They include things such as having a strong, clear, positive purpose (the slogan “Wikipedia is an encyclopedia” is a surprisingly powerful reminder that keeps editors honest); assuming good faith and being courteous; refraining from taking sides and being radically transparent.

It’s a no-nonsense “lessons learned” book that might otherwise find itself occupying shelf space next to Steven Bartlett’s Diary of a CEO (subtitle: The 33 Laws of Business and Life) – but Wikipedia’s ubiquity, and the way it has dramatically bucked the trend of online toxicity – make it potentially far more significant,I meet Wales at his publishers’ offices near the British Museum in London,It’s a clear autumn morning and we sit in the Duncan Grant-inspired “author’s room” amid brightly coloured cushions and murals,He wears a creased pink linen shirt and slurps coffee while we wait for pastries,It’s the second time we’ve met – the first was at a dinner in July to give journalists a taste of the book, where he showed himself able to hold forth in front of a room of literary editors and reporters in press conference mode.

Here he seems a bit more hesitant, chuckling nervously, prone to delivering answers with great big bracketed sections that make us both forget what the question was.“I’m a little bit too shy to do interviews, even though I do,” he tells me, about the process of talking to people about Seven Rules.Traces of his native Alabama have mostly disappeared from his accent after years of living in London, and there’s even the occasional English glottal stop.He moved here in 2012 to be with Kate Garvey, a former aide to Tony Blair, whom he met at the World Economic Forum in Davos.They are married and have two daughters together.

“It’s a funny thing when I say that I’m shy to people, because they’re like, ‘Oh, you do a lot of public speaking’, but yeah, that’s not the same thing.” You wouldn’t call him socially awkward, exactly, but neither does he present as completely Ted Talk ready.Instead, he’s ordinary, approachable, with none of the bombast of some of his internet mogul peers.Wales turns 60 next year.His direct contemporaries include PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, and Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin.

All of them have had profound influence on our lives, but only one of them has failed to become a billionaire.There’s an easy story to tell about this; that as “the good guy of the internet” Wales used his entrepreneurial skills in the service of a higher calling.What does he make of that kind of talk? “I don’t know.I mean, it’s embarrassing,” he laughs.Is there a part of him that likes the epithet, though? “Of course, no, it’s great.

I mean, I’m very proud of Wikipedia.” But the idea that he renounced astronomical amounts of money in order to make the world a better place is wide of the mark.“I don’t see it like that.Early in my career, in the career of Wikipedia, a lot of journalists were asking that question, thinking I was going to be some kind of communist because, like, why would you be doing this thing as a nonprofit? But I’m not.I’m actually quite in favour of business and capitalism and all that.

” (He’s currently president of Fandom, an ad-funded entertainment site that hosts user-edited pages, owned by private equity firm TPG Capital).“I just like doing interesting things.So I get up and I just do the most interesting thing I can think of.And Wikipedia is super interesting … I go and I visit with Wikipedians all around the world and go to schools and things like that.I meet prime ministers.

”“And actually, on the money front,” he continues, “I live here in London.How many bankers in the City make far more money than I ever will? Loads of them.How many of their lives are dramatically less interesting than mine? I would say almost all of them.”Back in 2006, comedian Stephen Colbert did a bit about Wikipedia, saying it was the harbinger of a distorted form of reality called “Wikiality” (“if enough other users agree … it becomes true”), and encouraging viewers of The Colbert Report to introduce edits containing bogus stats about elephants.It almost collapsed the site.

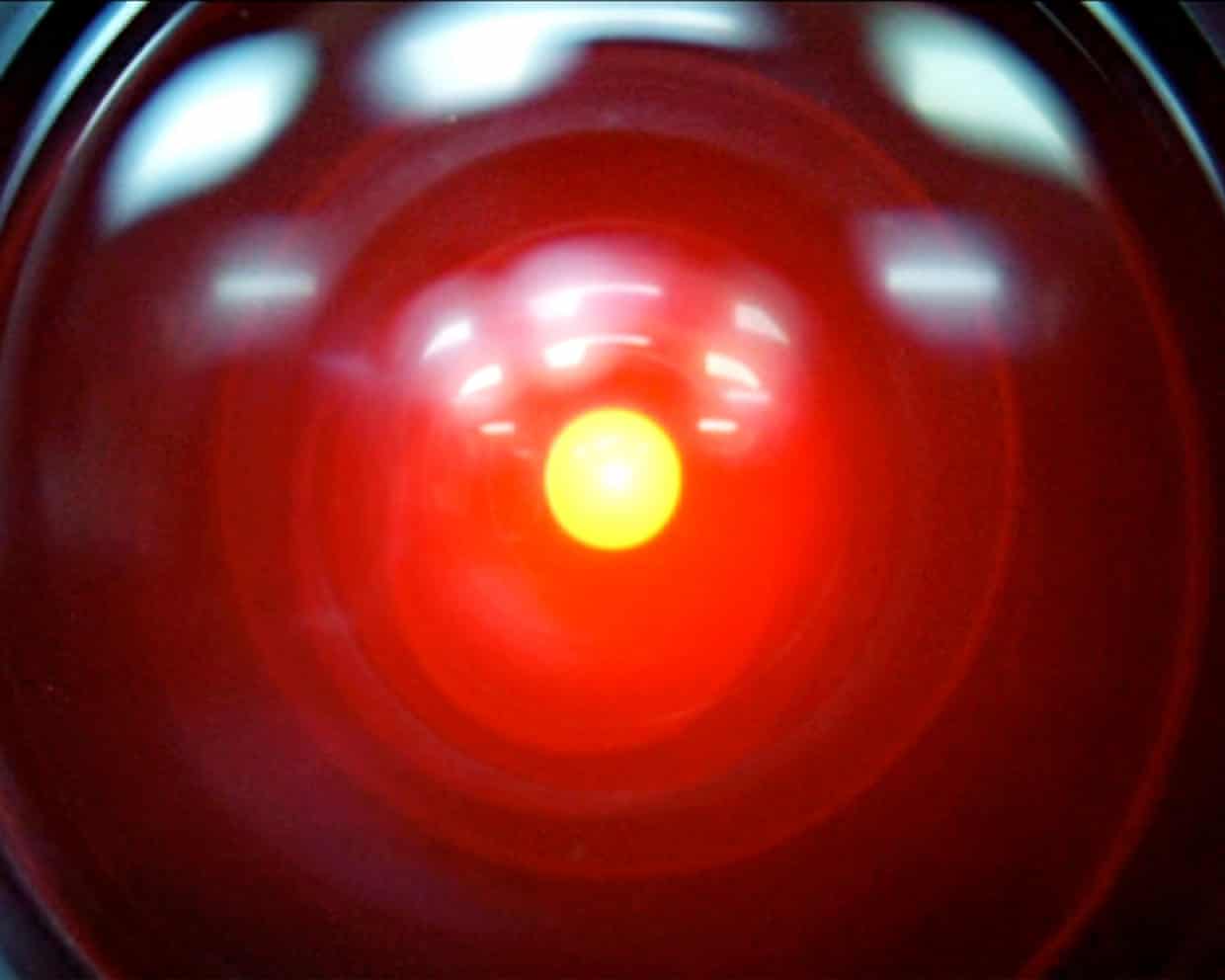

Fast forward to 2025 and it seems that Wikipedia might be the antidote to “alternative facts”, with lessons not just for the web, but for society more broadly.Not everyone is convinced.On the day I meet Wales, Musk suggests to his 228 million followers on X that “Wikipedia should be called Wokipedia (or Dickipedia 😂)”.It’s the latest salvo in Musk’s rolling campaign to discredit the nonprofit site and generate interest in his own “Grokipedia” project, a plan for an AI-based encyclopedia that will be “a massive improvement over Wikipedia” and “a necessary step towards the xAI goal of understanding the universe”.Musk’s hostility aside, does Wales see artificial intelligence in general as a threat? If people are increasingly relying on AI summaries, might Wikipedia’s dominance turn out to have been a blip? “I don’t think so,” he says, “but, I mean, that’s obviously on a lot of people’s minds these days.

” It would be ironic, given that the site’s free licensing model means it can be used by anyone for anything – including as training data for large language models.“There are definitely threats to the web, but they’re not necessarily coming from AI,” he says.“I think the bigger threat is the rise of authoritarianism, governments, regulations, which make it harder to have a truly open global web where people are free to share ideas.” It’s true that Wikipedia is blocked in China, and faces sporadic censorship in Russia and elsewhere.Wales’s stance on this is not to give an inch – he has said: “We have a very firm policy, never breached, to never cooperate with government censorship in any region of the world.

”What about his billionaire peers? Do they have any influence? Musk messaged him the morning after the 2024 US presidential election, not to crow over Donald Trump’s victory, but to complain about a Wikipedia article in which a friend of his was described as “far right”.When Wales checked, it had already been changed, and he judged that it was a reasonable call, though he won’t tell me whose page it was.“I mean, the circumstances were a little surprising, but it’s, you know, completely legitimate.” He says people are always messaging him saying they’ve seen something on a page that doesn’t look right.Wales will take a look, but he doesn’t hand out favours: changes have to conform to the usual rules about fairness and proper sourcing.

Does he still regard Musk, the world’s richest man, as a friend? “Friends is probably a little strong.I mean, not, not that –” he sputters, editing himself in real time.“I want to be careful how I say that, only because I’ve met him maybe five or six times, so that I would be overstating to say friends.We’ve been friendly, and even now he’s much nicer to me in private than you might think.I mean, he’s got a big public persona, and that’s a little bit different from the private Elon, who I think is more thoughtful.

” It’s a weird strategy, isn’t it, to be so aggressive in public, if that’s not what you’re actually like? “I don’t know,It’s a good question,I have this general rule of, like, I can’t speculate about what goes on in Elon Musk’s head,I have no idea – I’m as at a loss as anybody,”Musk’s attacks are rooted in a belief that Wikipedia has an in-built leftwing bias.

In this, he joins the likes of Tucker Carlson, who recently said: “It’s an emergency, in my opinion, that Wikipedia is completely dishonest.” There’s a sense that Maga has Wikipedia in its sights.Wales is frustrated by this, but isn’t going to get drawn into a slanging match.“It’s annoying, but one of the things that I’ve said to [Musk] is if you really want to help, the right way is not to misstate the facts,” he says firmly.“Saying that Wikipedia has been taken over by ‘woke’ activists is just false.

But if you think Wikipedia has some bias in it – and, of course, that’s always something we have to think about and grapple with – then going around saying it has been taken over by ‘crazed trans Hamas supporters’, or whatever you think, is doing two things.One, it’s telling kind and thoughtful conservatives that Wikipedia is not the place for you, and that’s a shame.And it’s also telling [activists], here’s your new home, which means we have to deal with them.We want to communicate to everybody that Wikipedia is not a very comfortable place for extremists.If you want to rant about things and you want to be super biased, then go on, write your own blog.

What we’re looking for is kind and thoughtful people who care more about getting it right and being calm and factual.”Seven Rules is particularly strong on the importance of not taking sides, arguing that if people believe an institution isn’t neutral, trust evaporates.Crucially, that happens even if it’s biased in your favour.Wales cites work by Cory Clark at the University of Pennsylvania that looked at how people responded to political stands taken by all sorts of organisations, from newspapers to dental clinics to sports leagues.“When people thought a group was politicised against their own political position, they trusted the group less.

No surprise there.But when people thought the group had taken sides and was politically aligned with them … they still trusted them less.”He brings up his own example: “I remember during the first Trump administration reading a hard news story in the Washington Post, which was doing great reporting, and I loved this story.But at the end, I’m like: ‘That was a rant against Donald Trump, and they interpreted every piece of evidence in the most negative possible way.’” This annoyed him even though he was on the “side” of the reporter (earlier, Wales tells me: “I really can’t bear Donald Trump, he’s just appalling.

”).“Do I feel like I’ve gotten the full picture to make up my own mind, or do I feel like I’ve been fed something that I probably already agree with? I think that’s problematic.”Sign up to Inside SaturdayThe only way to get a look behind the scenes of the Saturday magazine.Sign up to get the inside story from our top writers as well as all the must-read articles and columns, delivered to your inbox every weekend.after newsletter promotionAt the same time, neutrality and civility has its limits, doesn’t it? I mention a clever op-ed by Larry David that made this point, called My Dinner With Adolf, in which the comedian imagines breaking bread with the worst man in history.

He ends with the line: “I must say, mein Führer, I’m so thankful I came.Although we disagree on many issues, it doesn’t mean that we have to hate each other.” What does Wales think about the risk that, in giving a fair hearing to all sides, you can fail in the moral duty to call out real wickedness?“So I think we can make a distinction here between what I ought to do, what you ought to do, versus what an encyclopedia ought to do,” he says.“Hitler is always a terrible example, but it actually is a great example in this case: it’s like, the Hitler entry doesn’t have to be a rant against Hitler.You just write down what he did, and it’s a damning indictment right there … you don’t need to add ‘PS, he’s a horrible person’.

You just say: ‘These are the facts, draw your own conclusions.’” In Seven Rules, he quotes a Ukrainian Wikipedia editor who puts his personal feeling to one side to maintain the policy of strict neutrality: “The neutral facts are still on the side of Ukraine, right?”This separation of fact and sentiment seems pretty unusual nowadays.It’s no great mystery why: in the book, Wales talks about “an entire class of ‘content creators’ who have effectively been trained by social media algorithms to play up outrage, fear, and hate at every opportunity”.Part of the reason this has happened is because of the lack of guiding principles among web 2.0’s major players

Pat Cummins ruled out of first Ashes Test, with Steve Smith to captain Australia

Pat Cummins has lost the race to be fit for the first Ashes Test as he continues his recovery from a stress injury in his back, with Steve Smith to reassume the captaincy of Australia in the series opener against England next month.Cummins has not bowled since Australia’s 3-0 series defeat of West Indies in July and was in serious doubt for the match in Perth on 21 November. After months of speculation over whether he would recover in time, Cricket Australia on Monday finally confirmed that the quick would have to sit out the game at Optus Stadium.The 32-year-old’s acumen with the ball in hand and his presence as a leader on the field will be sorely missed, and his absence comes as a blow to Australia’s hopes of retaining the Ashes urn.The 32-year-old has resumed running and expects to return to bowling imminently, and while an exact date has not been put on any return to full fitness, Australia coach Andrew McDonald said he was hopeful he would be able to call on Cummins for the second Test in Brisbane

Mexico Grand Prix: Norris claims dominant win to lead drivers’ standings – as it happened

Giles Richards has filed his report on a hugely important race – and result – in the battle for the drivers’ championship:Max Verstappen also speaks to TV:“It was very hectic at the beginning of the race for me. I almost crashed. Everyone around me was on soft tyres and we were on medium, so it was a bit of a struggle. It was about surviving the first stint. Once we bolted on the softs I think we were a little bit more competitive and happier

Lando Norris hits the front in title race with emphatic F1 Mexico City GP win

If timing is key in any race, Lando Norris might just have taken the bell with absolutely impeccable judgment. His victory at the Mexico City Grand Prix with a consummate drive from pole to flag has catapulted him into the lead of an intense title fight at exactly the right moment. Norris has momentum at the very point the championship enters its decisive phase.With his title rivals Oscar Piastri – Norris’s McLaren teammate – managing only fifth and Red Bull’s Max Verstappen third at the Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez, Norris has the edge at a crucial juncture with four meetings remaining. Ferrari’s Charles Leclerc finished in second, while Britain’s Oliver Bearman took a career-best fourth place with a superb drive for Haas

Saracens’ Noah Caluori called up by England for autumn internationals

Noah Caluori, the 19-year-old Saracens wing, has been named in England’s autumn internationals squad by Steve Borthwick.Caluori burst on to the Prem scene by scoring five tries against Sale on 18 October and, as England gear up for a busy November featuring four Tests, Borthwick has called up the uncapped youngster after initially inviting him to a training camp last week. The 36-player squad, including 19 forwards and 17 backs, gathered at Pennyhill Park in Surrey on Sunday night.Caluori made his second Prem start for Saracens in the defeat by table-topping Northampton on Friday. He had a considerably quieter night than the phenomenal display against Sale, and was given a severe defensive test by the Saints’ all-court attacking game

New York Jets legend Nick Mangold dies aged 41 while seeking kidney transplant

Nick Mangold, a hugely popular player during his 11-season career with the New York Jets, has died at the age of 41.Earlier this month, Mangold said he had been undergoing dialysis and needed a kidney transplant. He sought help from fans of the Jets and Ohio State, where he was a star in college.“In 2006, I was diagnosed with a genetic defect that has led to chronic kidney disease. After a rough summer, I’m undergoing dialysis as we look for a kidney transplant,” he wrote at the time

Shaun Wane requires herculean Ashes effort after England’s Wembley mauling

The scoreline alone offers concrete evidence of how underwhelming England were against Australia in the first Ashes Test on Saturday, but if anyone needed further proof, a glimpse around the Wembley crowd was somewhat telling, too.As a one-sided contest ebbed towards a predictable conclusion, there were cheers among those sitting near the press box. Not for an England try, but for a paper aeroplane crafted by a home supporter that had successfully made its way from the top of one tier on to the pitch. It was about the only thing that went right for those of an English persuasion.The beauty of a three-Test series is that no matter what happens in the first match there is an opportunity to bounce back

Could the internet go offline? Inside the fragile system holding the modern world together

Fare game: what the battle between taxis and Uber means for your airport trip in Sydney and Melbourne

Amazon strategised about keeping its datacentres’ full water use secret, leaked document shows

AI models may be developing their own ‘survival drive’, researchers say

‘He’s one of the few politicians who likes crypto’: my day with the UK tech bros hosting Nigel Farage

‘Sycophantic’ AI chatbots tell users what they want to hear, study shows