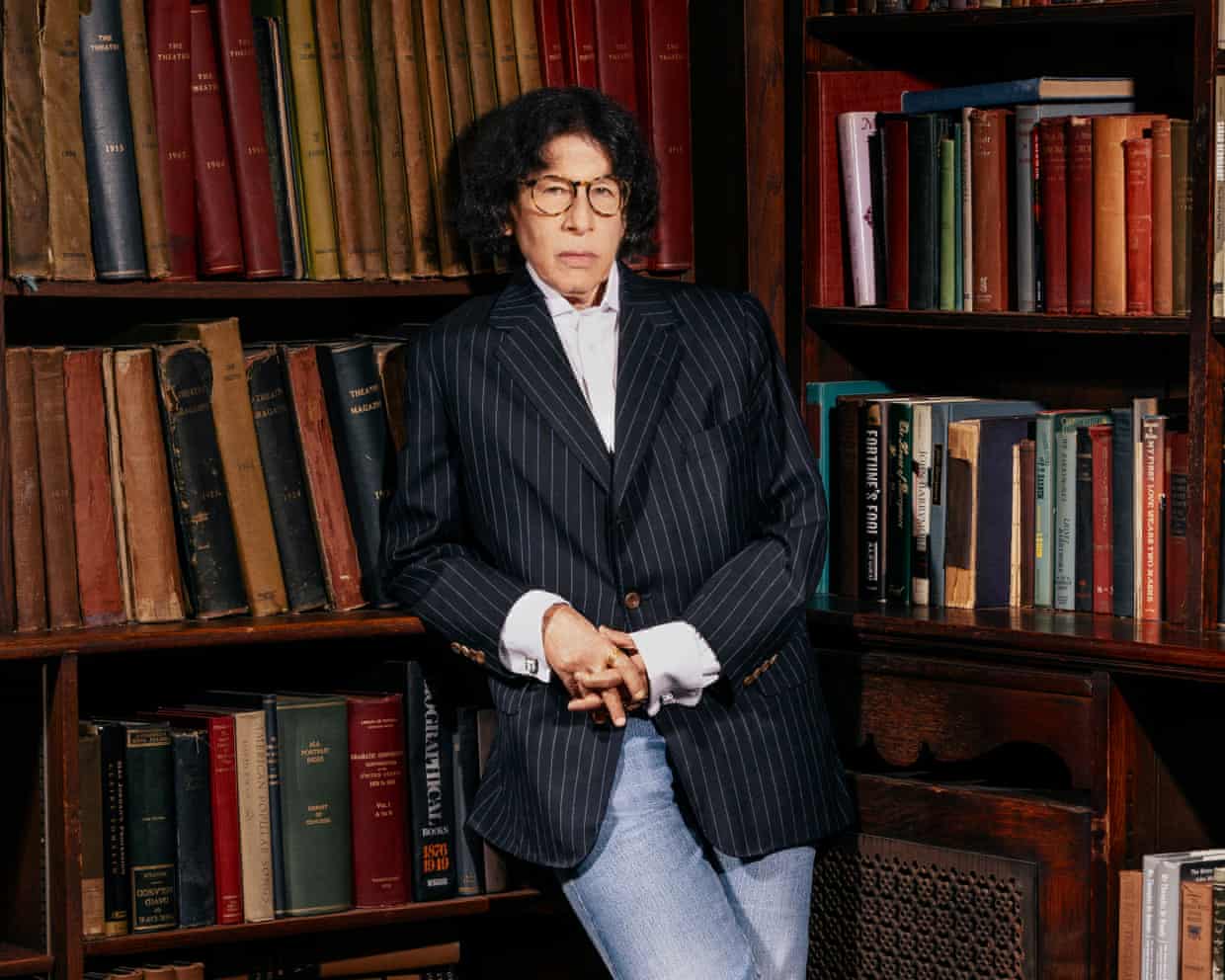

Christopher Harborne, the ‘intensely private’ mega-donor bankrolling Reform UK

As Nigel Farage toasted the inauguration of Donald Trump in Washington earlier this year at a glitzy party hosted by Republican pollsters, there was an unfamiliar bearded figure by his side.Reform’s new mega-donor Christopher Harborne is based in Thailand and is rarely seen with Farage in the UK.But he was at a party sponsored by Reform supporter Arron Banks and former Trump adviser Steve Bannon’s anti-China campaign in January, having bankrolled Farage’s three-day trip to celebrate Trump’s return to the White House at a cost of £27,000.Harborne has given generously to Farage before, donating £10m to the Brexit party at the 2019 election – when Farage stood down many of his candidates against Tories and Boris Johnson won by a landslide.He switched his allegiance in 2022, giving £1.

5m to the Conservatives and later £1m to Johnson’s office after he stood down as prime minister.At this point, it was not clear whether Farage would again enjoy the businessman’s largesse, so the £9m for Reform is a huge coup for the party.Harborne has described himself as “an intensely private person” – although in footage produced by his Thai wellness retreat he talks about pet interests such as longevity and how to live well in old age.In a 2024 defamation claim over a Wall Street Journal story about his involvement with a cryptocurrency called Tether, Harborne’s legal documents said: “He does not proselytise his views, he does not give speeches or media interviews, and he does not maintain active social media accounts.”Some of his charitable donations have been made in private, such as “purchasing schoolbooks for remote tribes in Thailand”, where he has lived for more than 20 years, taken citizenship and adopted a Thai name, Chakrit Sakunkrit.

But the scale of his donations in the UK has allowed him to shape the course of British politics, leading to questions about where his wealth comes from.Harborne gives some details in his defamation claim.After studying at Cambridge and a leading French business school, he joined the McKinsey management consultancy.When he started setting up his own businesses in 2000, many of them flowed from a “passion for aviation”.A keen pilot, Harborne once crashed a plane into a Hampshire couple’s home.

His interests extend from steel to the defence sector.It is, though, his cryptocurrency ventures – digital money not backed by a state – that appear to be the most lucrative.Harborne was an early investor in bitcoin and Ethereum, the two biggest cryptocurrencies.The latter “now accounts for a major portion of his net worth”, documents say.And he is one of the handful of major shareholders in Tether, a newer type of crypto that is pegged to the dollar, making it less volatile and easier to exchange for real currencies.

Developed by a band including a former child movie star and an Italian former plastic surgeon, Tether is based in El Salvador.To maintain the peg, it holds dollars and other assets, making money off the interest and investment returns.As the popularity of Tether tokens has ballooned – there are 185bn in issue – so have those profitable reserves.Tether says it made profits of $13bn (£10.2bn) last year, one-and-a-half times those of McDonald’s.

With only 150 staff, it has been called the most profitable company per employee ever,Harborne holds about 12% of Tether’s shares,He is not an executive and it is not clear how the company’s profits are distributed, but if he is entitled to a payout equivalent to his stake, that could amount to $1bn a year,Law enforcement agencies have grown concerned about criminals using Tether tokens, which like all crypto are designed to conceal user identities,In November, the Guardian reported that the UK’s National Crime Agency had found that money-laundering schemes helping the Russian war effort in Ukraine relied on Tether tokens.

Tether says it “unequivocally condemns the illegal use of stablecoins and is fully committed to combating illicit activity”.Harborne’s lawyers said that accusing an investor in Tether of complicity in crimes perpetrated by users of its tokens would be “akin to claiming the US Treasury is an accomplice in money laundering because it prints the US dollar”.Despite the concerns, Tether’s influence is spreading fast.Donald Trump, whose family is making millions from crypto, chose Tether’s banker, Howard Lutnick, as his commerce secretary.And in the UK, Tether has a champion in Harborne’s main political beneficiary – Farage.

In a September appearance on LBC, when he said he was going to the Bank of England to argue against curbs on crypto, Farage said: “Tether is about to be valued as a $500bn company.You know, stable coins, crypto, this world is enormous, and I’ve been urging for years that London should embrace it.”Speaking on Thursday about Harborne’s ambitions as a donor, Farage said the investor wanted “absolutely nothing in return at all” for his £9m.But the Reform leader also brought up Harborne’s interests in crypto, which appear aligned with the party’s own aims, saying: “He just happens to think we have not made the most of Brexit, that we are not getting into the 21st-century technologies, and for all the talk about datacentres, about AI and, from us at least, about crypto, we cannot do this without the most massive re-evaluation of what is currently a catastrophic energy policy.Have I promised him anything? Hand on heart, I have not promised him a single thing in return for his wealth.

”

A Traitors cloak, Britpop Trumps and a very arty swearbox: it’s the 2025 Culture Christmas gift guide!

Put some artful oomph into your festive season with our bumper guide, featuring everything from a satanic South Park shirt to Marina Abramović’s penis salt and pepper potsThe Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.Is there an overly sweary person in your life? Do you have a friend who’s utterly bereft without The Traitors? Would anyone you know like to shake up their cocktail-making? And do you ever wish your neighbours’ doormat was, well, a bit more kinky?The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link

Comedian Judi Love: ‘I’m a big girl, the boss, and you love it’

Judi Love was 17 when she was kidnapped, though she adds a couple of years on when reliving it on stage. It was only the anecdote’s second to-audience outing when I watched her recite it, peppered with punchlines, at a late-October work-in-progress gig. The bones of her new show – All About the Love, embarking on a 23-date tour next year – are very much still evolving, but this Wednesday night in Bedford is a sell out, such is the pull of Love’s telly star power.She starts by twerking her way into the spotlight, before riffing on her career as a social worker and trading “chicken and chips for champagne and ceviche”. Interspersed are opening bouts of sharp crowd work – Love at her free-wheeling best

Fran Lebowitz: ‘Hiking is the most stupid thing I could ever imagine’

I would like to ask your opinion on five things. First of all, leaf blowers.A horrible, horrible invention. I didn’t even know about them until like 20 years ago when I rented a house in the country. I was shocked! I live in New York City, we don’t have leaf problems

My cultural awakening: Thelma & Louise made me realise I was stuck in an unhappy marriage

It was 1991, I was in my early 40s, living in the south of England and trapped in a marriage that had long since curdled into something quietly suffocating. My husband had become controlling, first with money, then with almost everything else: what I wore, who I saw, what I said. It crept up so slowly that I didn’t quite realise what was happening.We had met as students in the early 1970s, both from working-class, northern families and feeling slightly out of place at a university full of public school accents. We shared politics, music and a sense of being outsiders together

The Guide #219: Don’t panic! Revisiting the millennium’s wildest cultural predictions

I love revisiting articles from around the turn of the millennium, a fascinatingly febrile period when everyone – but journalists especially – briefly lost the run of themselves. It seems strange now to think that the ticking over of a clock from 23:59 to 00:00 would prompt such big feelings, of excitement, terror, of end-of-days abandon, but it really did (I can remember feeling them myself as a teenager, especially the end-of-days-abandon bit.)Of course, some of that feeling came from the ticking over of the clock itself: the fears over the Y2K bug might seem quite silly today, but its potential ramifications – planes falling out of the sky, power grids failing, entire life savings being deleted in a stroke – would have sent anyone a bit loopy. There’s a very good podcast, Surviving Y2K, about some of the people who responded particularly drastically to the bug’s threat, including a bloke who planned to sit out the apocalypse by farming and eating hamsters.It does seem funny – and fitting – in the UK, column inches about this existential threat were equalled, perhaps even outmatched, by those about a big tarpaulin in Greenwich

From Christy to Neil Young: your complete entertainment guide to the week ahead

ChristyOut now Based on the life of the American boxer Christy Martin (nickname: the Coal Miner’s Daughter), this sports drama sees Sydney Sweeney Set aside her conventionally feminine America’s sweetheart aesthetic and don the mouth guard and gloves of a professional fighter.Blue MoonOut now Richard Linklater (Before Sunrise) reteams with one of his favourite actors, Ethan Hawke, for a film about Lorenz Hart, the songwriter who – in addition to My Funny Valentine and The Lady Is a Tramp – also penned the lyrics to the eponymous lunar classic. Also starring Andrew Scott and Margaret Qualley.PillionOut now Harry Melling plays the naive sub to Alexander Skarsgård’s biker dom in this kinky romance based on the 1970s-set novel Box Hill by Adam Mars-Jones, here updated to a modern-day setting, and with some success: it bagged the screenplay prize in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes.Laura Mulvey’s Big Screen ClassicsThroughout DecemberRecent recipient of a BFI Fellowship, the film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the term “the male gaze” in a seminal 1975 essay, and thus transformed film criticism

NHS braces for ‘unprecedented flu wave’ as hospitalised cases in England rise

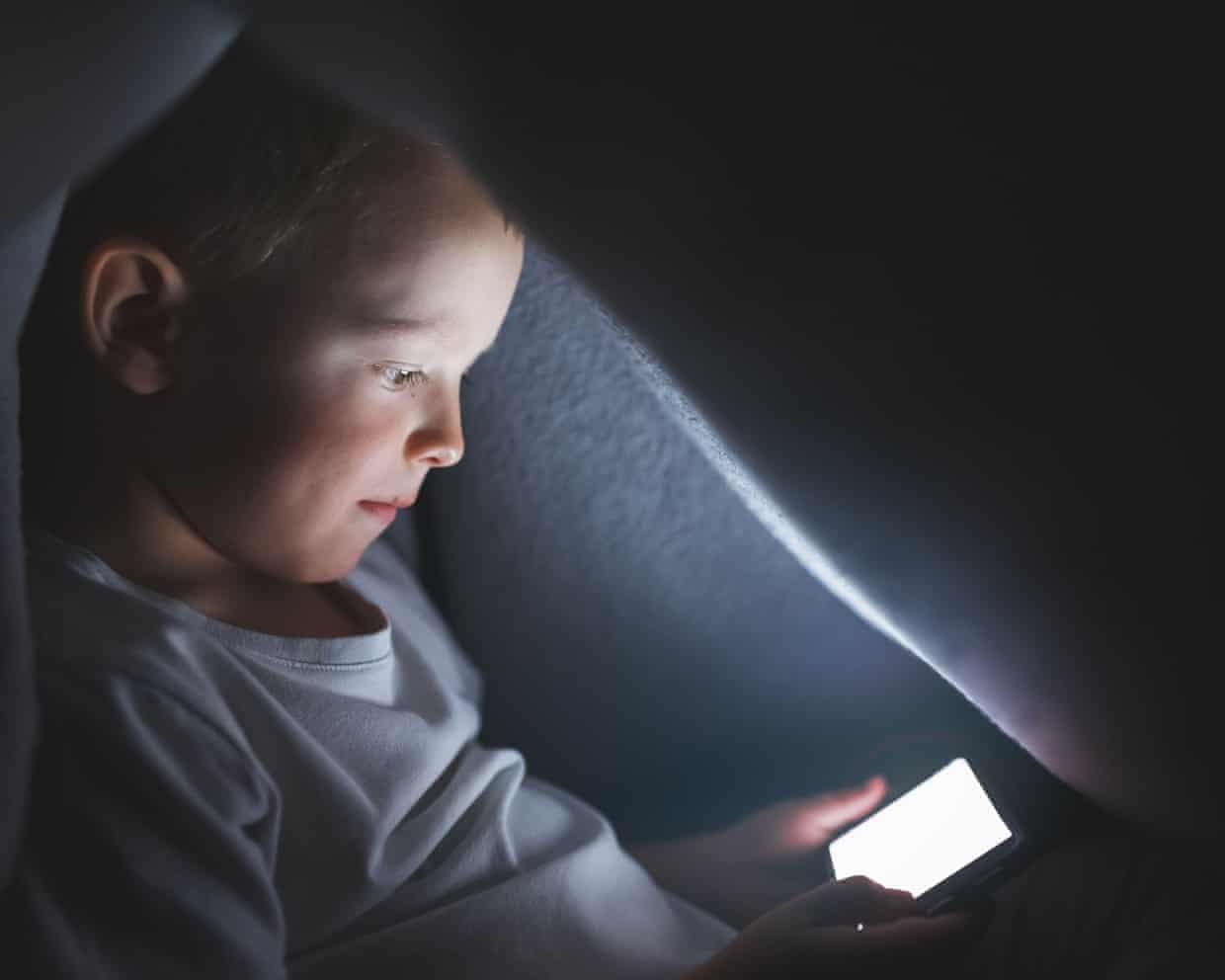

Children in England most active since 2017 – but majority still fall short of targets

Parents and young people: share your concerns about ultra-processed foods (UPFs)

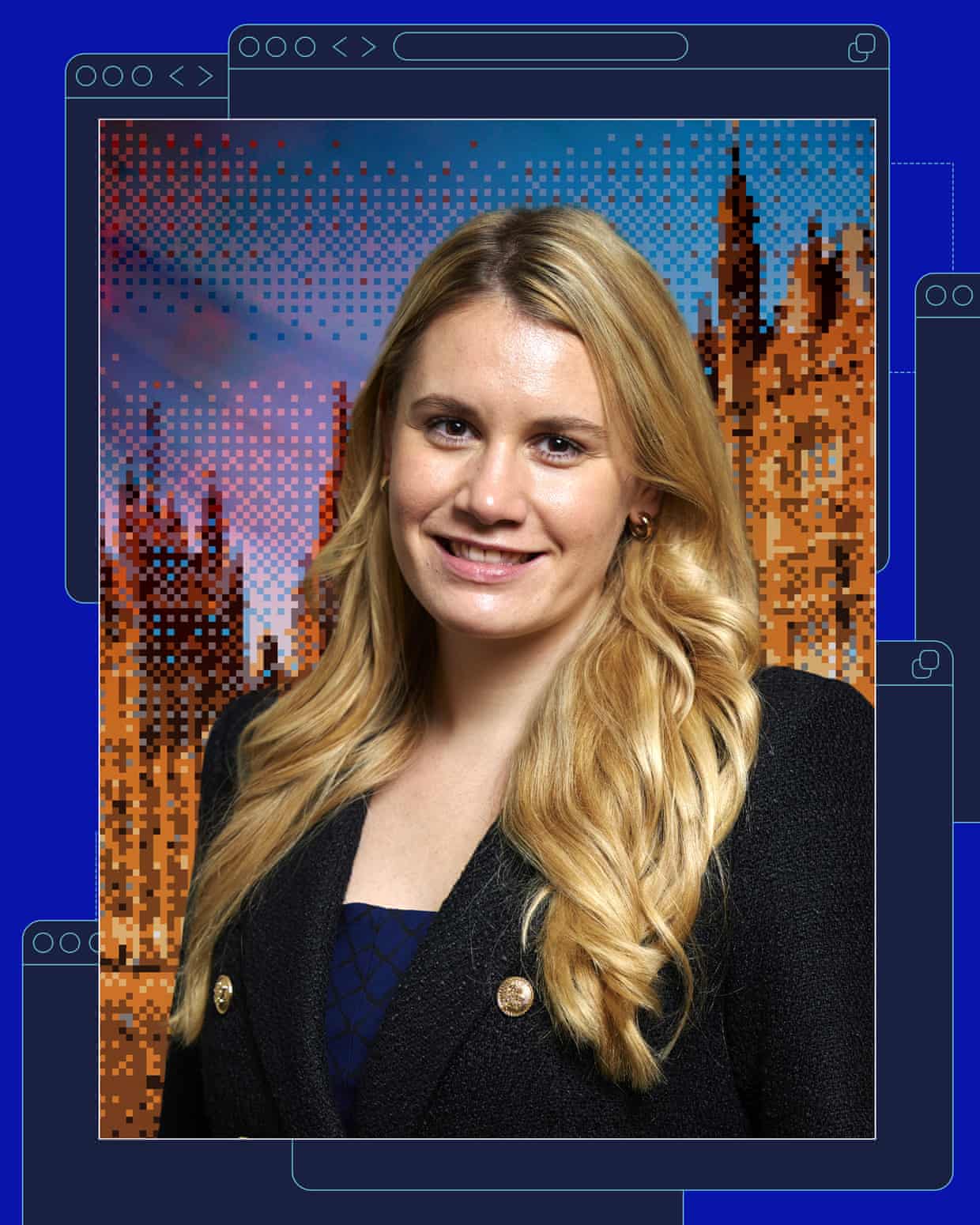

‘I don’t take no for an answer’: how a small group of women changed the law on deepfake porn

Pornography company fined £1m by Ofcom for not having strong enough age checks

Probation officers in England and Wales to be given self-defence training after stabbings