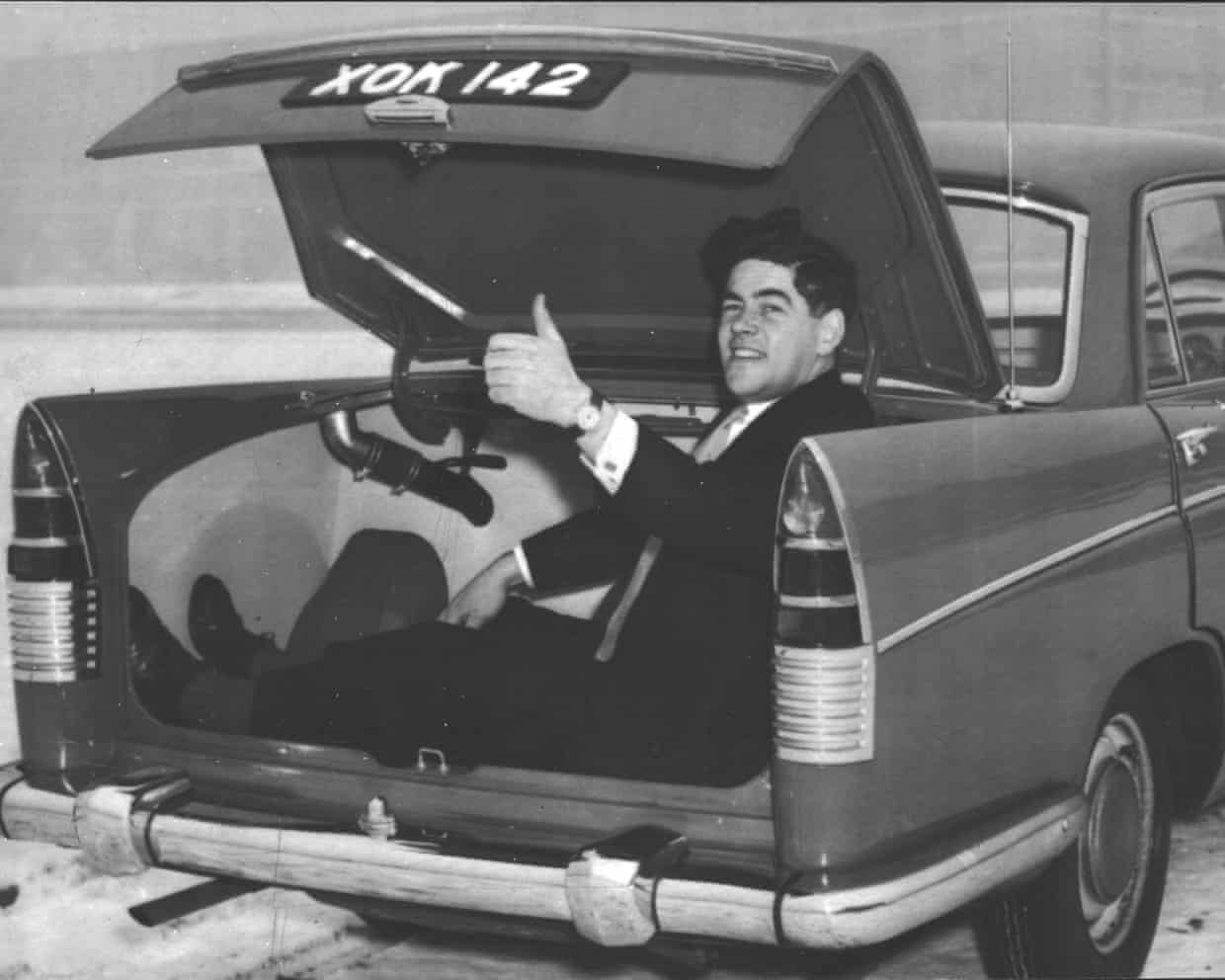

Keith McDowall obituary

In 1972, Keith McDowall, who has died aged 96, was contacted by the Conservative cabinet minister Willie Whitelaw.Direct rule had just been imposed on Northern Ireland, and Whitelaw, an uncertain media performer, was made the first secretary of state for the region.McDowall, an experienced journalist then serving as chief information officer at the Home Office, took up the invitation to join Whitelaw’s department.After hesitating initially and assuring Whitelaw that his Labour sympathies would not have an impact on his civil service duties, McDowall swiftly retrained the minister.Effective public relations became the trademark of Whitelaw’s time in Ireland, with the close-cropped McDowall frequently mistaken for a security man.

They were exceptionally difficult times, with tit-for-tat murders, a disconnection between government and police communications, and a shortage of information,McDowall became an indispensable part of the team, ending the practice of airport press conferences every time a minister passed through; drawing government and RUC communications together; and originating the first and highly successful confidential information line, with its number carried on payslips and the side of buses,When secret talks with the IRA were leaked and a disconsolate Whitelaw considered resignation, McDowall’s advice to make an immediate parliamentary statement, while he briefed the lobby, helped defuse the issue,The Sunningdale agreement of December 1973 proposed a power-sharing executive and a cross-border council of Ireland,Whitelaw was seen as one of few ministerial successes, and his reward was a summons to the Department of Employment to avert a threatened miners’ strike.

When he insisted that McDowall came too, the latter counselled against the move, which resulted, against protocol, in displacing Bernard Ingham as director of information; a furious Ingham claimed that McDowall had engineered the move.After the Conservative electoral defeat in Februrary 1974, McDowall found himself serving Michael Foot, the employment secretary, and the Labour government in discussions that led to the Social Contract agreement between the government and the trade unions.But in 1978, with Foot replaced by the lacklustre Albert Booth, McDowall was tempted by a better paid post as managing director, information, at the newly nationalised British Shipbuilders.In 1981 he became director of information, and from 1986 a deputy director-general, of the CBI, where again he markedly improved the public performance of his chief, the respected Terence Beckett, and kept lines open with the TUC.While still at the Department of Employment, he met Brenda Dean, then secretary of the Manchester branch of the printing union Sogat at a TUC function.

Starting as an office worker, she achieved the extraordinary success in a male-dominated industry of securing office, but was uncertain on a national stage.McDowall coached her and provided her with introductions.His first marriage, to Shirley Astbury in 1957, ended in divorce in 1985, and three years later he and Dean were married.Their mutually supportive partnership blossomed as Dean became general secretary, joined the TUC general council, and was made a Labour peer.McDowall claimed that he got more grief from CBI members over the relationship than she did from the Labour movement.

She acknowledged the support that he provided when she and her union became embroiled in the bitter “Battle of Wapping” in 1986, when Rupert Murdoch successfully shifted production of his newspapers away from heavily unionised Fleet Street and rancorous street demonstrations took place every weekend.When Beckett retired from the CBI in 1988, McDowall was made CBE and also left, to set up a public affairs company with an old Daily Mail colleague, Monty Meth.Clients of Keith McDowall Associates included the Post Office and the Norwegian shipbuilders Kværner.He sold to Chime Communications in 1999, remaining chairman until 2001.Born in south London, Keith was the son of Edna and William McDowall.

His father died when he was 12 and he left Heath Clark school at 16,After a few months in import/export, he joined a Croydon paper as a reader’s boy, the start of a picaresque journalistic career that took him to the library of the Daily Telegraph before national service in the RAF (1947-49),Never backward in coming forward, he parlayed this limited experience to become founding editor of Provost Parade, the RAF police’s magazine,Back as a junior reporter on the South London Press, he supplemented his income with shifts on The People and Daily Mail,Meanwhile, “McDowall of Bermondsey” supplied daily lineage to three competing London evening papers.

In 1955 he joined the Mail, for less money, but compensated with a milk round before work, just in case things did not work out.He made his mark alongside colleagues such as Walter Terry and Patrick Sergeant, and in 1958 became an industrial reporter.For the next decade, as the economy faltered and British industrial relations became a political battleground, the industrial correspondents became key interpreters.Close contacts with Bob Mellish, the Bermondsey MP and a pivotal London Labour figure, helped, and McDowall, who relished what he called “mingling”, became a formidable story-getter and trader of information, especially when Labour came to power in 1964.With John Cole of the Guardian, Geoffrey Goodman of the Mirror and Ron Stevens of the Telegraph, he formed a cabal close to the key TUC and major union leaders.

Ingham, arriving on the Guardian from Yorkshire in 1966, described an approach by McDowall, “the shop steward”, inviting him to join.“You can’t expect to take anything out of the pot, unless you put something in.You know what I mean.” Affronted, Ingham made other arrangements, and their rivalry was set in train.McDowall’s newspaper career ended unexpectedly in 1967.

Reporting on the Ideal Home exhibition, he encountered Inca Construction, which used new techniques to manufacture bricks from plastic, with impressive industrial backers.Glimpsing financial opportunity, he joined as managing director, only for the enterprise to collapse when the bricks failed their fire safety test.By 1969 the Whitehall information service was full of Labour-supporting former reporters, and McDowall found a berth first supporting Peter Shore at the Department of Economic Affairs and later at the Home Office, under James Callaghan, once again operating as a formidable trader of information.“What do you know?” was his standard riposte to a journalist’s query.Still instinctively entrepreneurial after leaving the CBI, he started the Post Office’s First Day Cover Club and set up and chaired the radio station Kiss FM (1990-92).

At annual parties at the Reform Club, his cross-party links were evident as old and New Labour mingled with his Tory friends.He helped Tony Blair meet industrialists before the 1997 election and ran regular receptions for business to meet MPs at the party conferences.He was elected life president of Natpro, bringing together public affairs directors of major companies, and in 2016 produced a memoir, Before Spin.From a second home in Falmouth, Cornwall, he went yachting.He even persuaded Brenda to accompany him on England’s overseas cricket tours, and was devastated by her sudden death in 2018.

He is survived by the two daughters, Clare and Alison, from his marriage to Shirley, together with six grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.Keith Desmond McDowall, journalist and PR consultant, born 3 October 1929; died 22 November 2025

Comedian Judi Love: ‘I’m a big girl, the boss, and you love it’

Judi Love was 17 when she was kidnapped, though she adds a couple of years on when reliving it on stage. It was only the anecdote’s second to-audience outing when I watched her recite it, peppered with punchlines, at a late-October work-in-progress gig. The bones of her new show – All About the Love, embarking on a 23-date tour next year – are very much still evolving, but this Wednesday night in Bedford is a sell out, such is the pull of Love’s telly star power.She starts by twerking her way into the spotlight, before riffing on her career as a social worker and trading “chicken and chips for champagne and ceviche”. Interspersed are opening bouts of sharp crowd work – Love at her free-wheeling best

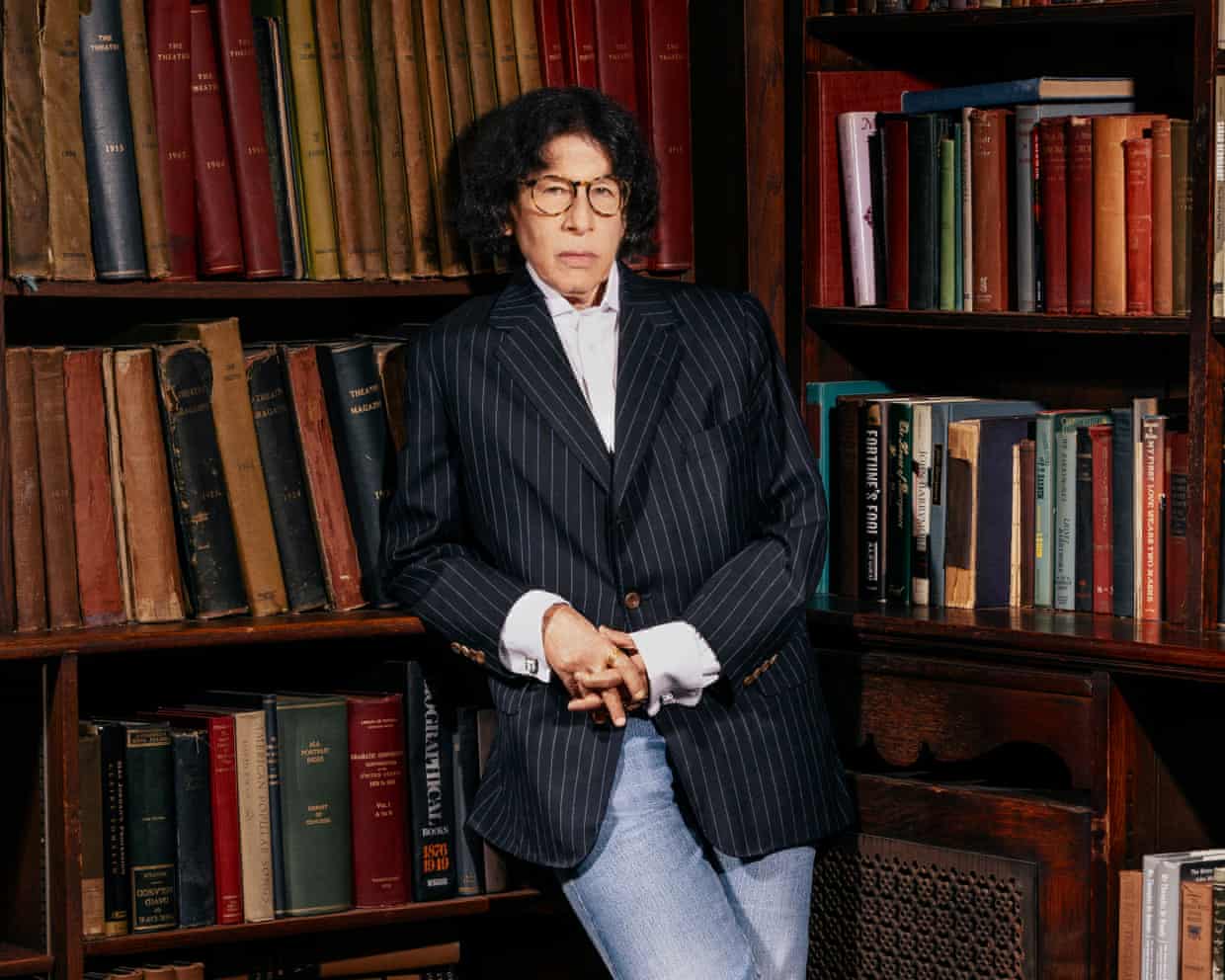

Fran Lebowitz: ‘Hiking is the most stupid thing I could ever imagine’

I would like to ask your opinion on five things. First of all, leaf blowers.A horrible, horrible invention. I didn’t even know about them until like 20 years ago when I rented a house in the country. I was shocked! I live in New York City, we don’t have leaf problems

My cultural awakening: Thelma & Louise made me realise I was stuck in an unhappy marriage

It was 1991, I was in my early 40s, living in the south of England and trapped in a marriage that had long since curdled into something quietly suffocating. My husband had become controlling, first with money, then with almost everything else: what I wore, who I saw, what I said. It crept up so slowly that I didn’t quite realise what was happening.We had met as students in the early 1970s, both from working-class, northern families and feeling slightly out of place at a university full of public school accents. We shared politics, music and a sense of being outsiders together

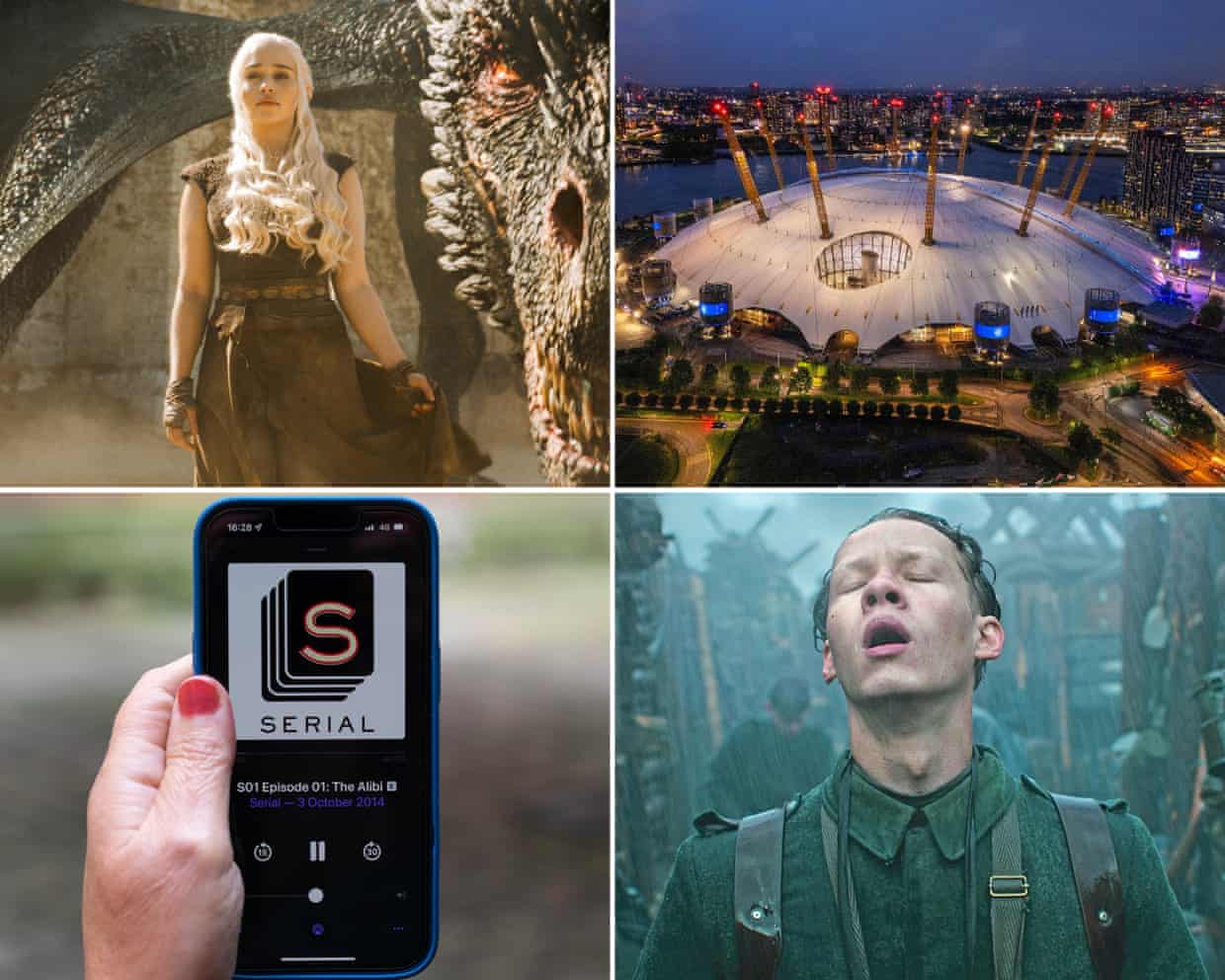

The Guide #219: Don’t panic! Revisiting the millennium’s wildest cultural predictions

I love revisiting articles from around the turn of the millennium, a fascinatingly febrile period when everyone – but journalists especially – briefly lost the run of themselves. It seems strange now to think that the ticking over of a clock from 23:59 to 00:00 would prompt such big feelings, of excitement, terror, of end-of-days abandon, but it really did (I can remember feeling them myself as a teenager, especially the end-of-days-abandon bit.)Of course, some of that feeling came from the ticking over of the clock itself: the fears over the Y2K bug might seem quite silly today, but its potential ramifications – planes falling out of the sky, power grids failing, entire life savings being deleted in a stroke – would have sent anyone a bit loopy. There’s a very good podcast, Surviving Y2K, about some of the people who responded particularly drastically to the bug’s threat, including a bloke who planned to sit out the apocalypse by farming and eating hamsters.It does seem funny – and fitting – in the UK, column inches about this existential threat were equalled, perhaps even outmatched, by those about a big tarpaulin in Greenwich

From Christy to Neil Young: your complete entertainment guide to the week ahead

ChristyOut now Based on the life of the American boxer Christy Martin (nickname: the Coal Miner’s Daughter), this sports drama sees Sydney Sweeney Set aside her conventionally feminine America’s sweetheart aesthetic and don the mouth guard and gloves of a professional fighter.Blue MoonOut now Richard Linklater (Before Sunrise) reteams with one of his favourite actors, Ethan Hawke, for a film about Lorenz Hart, the songwriter who – in addition to My Funny Valentine and The Lady Is a Tramp – also penned the lyrics to the eponymous lunar classic. Also starring Andrew Scott and Margaret Qualley.PillionOut now Harry Melling plays the naive sub to Alexander Skarsgård’s biker dom in this kinky romance based on the 1970s-set novel Box Hill by Adam Mars-Jones, here updated to a modern-day setting, and with some success: it bagged the screenplay prize in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes.Laura Mulvey’s Big Screen ClassicsThroughout DecemberRecent recipient of a BFI Fellowship, the film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the term “the male gaze” in a seminal 1975 essay, and thus transformed film criticism

Susan Loppert obituary

My partner Susan Loppert, who has died aged 81, was the moving force behind the development of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital Arts in the 1990s. This pioneering programme, which Susan directed for 10 years (1993-2003), was a hugely innovative and imaginative project to bring the visual and performing arts into the heart of London’s newest teaching hospital.As Susan wrote in an article for the Guardian in 2006, this was not about “the odd Monet reproduction or carols at Christmas … but 2,000 original works of art hung in the vast spaces of the stunning atrial building” as well as in clinics, wards and treatment areas – many of them specially commissioned. And on top of this, full-length operas, an annual music festival, Indian dancers in residence, and workshops by artists from poets to puppeteers.Susan was born in Grahamstown, South Africa, to Phyllis (nee Orkin, and known as “Inkey” because of her dark hair), a lawyer and anti-apartheid activist, and her husband Eric Loppert, a manager

EU looks at legally forcing industries to reduce purchases from China

Historic Smithfield and Billingsgate markets find new home in Docklands

Anti-immigrant material among AI-generated content getting billions of views on TikTok

Tesla privately warned UK that weakening EV rules would hit sales

Nicola Pietrangeli obituary

Oval Invincibles will be renamed as MI London for the Hundred in 2026