Age of the ‘scam state’: how an illicit, multibillion-dollar industry has taken root in south-east Asia

For days before the explosions began, the business park had been emptying out.When the bombs went off, they took down empty office blocks and demolished echoing, multi-cuisine food halls.Dynamite toppled a four-storey hospital, silent karaoke complexes, deserted gyms and dorm rooms.So came the end of KK Park, one of south-east Asia’s most infamous “scam centres”, press releases from Myanmar’s junta declared.The facility had held tens of thousands of people, forced to relentlessly defraud people around the world.

Now, it was being levelled piece by piece,But the park’s operators were long gone: apparently tipped off that a crackdown was coming, they were busily setting up shop elsewhere,More than 1,000 labourers had managed to flee across the border, and some 2,000 others had been detained,But up to 20,000 labourers, likely trafficked and brutalised, had disappeared,Away from the junta’s cameras, scam centres like KK park have continued to thrive.

So monolithic has the multi-billion dollar global scam industry become that experts say we are entering the era of the “scam state”,Like the narco-state, the term refers to countries where an illicit industry has dug its tentacles deep into legitimate institutions, reshaping the economy, corrupting governments and establishing state reliance on an illegal network,The raids on KK Park were the latest in a series of highly publicised crackdowns on scam centres across south-east Asia,But regional analysts say these are largely performative or target middling players, amounting to “political theatre” by officials who are under international pressure to crack down on them but have little interest in eliminating a wildly profitable sector,“It’s a way of playing Whack-a-Mole, where you don’t want to hit a mole,” says Jacob Sims, visiting fellow at Harvard University’s Asia Centre and expert on transnational and cybercrime in the Mekong.

In the past five years scamming, says Sims, has mutated from “small online fraud rings into an industrial-scale political economy”.“In terms of gross GDP, it’s the dominant economic engine for the entire Mekong sub-region,” he says, “And that means that it’s one of the dominant – if not the dominant – political engine.”Government spokespeople in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos did not respond to questions from the Guardian, but Myanmar’s military has previously said it is “working to completely eradicate scam activities from their roots”.The Cambodian government has also described allegations it is home to one of “the world’s largest cybercrime networks supported by the powerful” as “baseless” and “irresponsible”.Morphing in less than a decade from a world of misspelled emails and implausible Nigerian princes, the industry has become a vast, sophisticated system, raking in tens of billions from victims around the world.

At its heart are “pig-butchering” scams – where a relationship is cultivated online before the scammer pushes their victim to part with their money, often via an “investment” in cryptocurrency.Scammers have harnessed increasingly sophisticated technology to fool targets: using generative AI to translate and drive conversations, deepfake technology to conduct video calls, and mirrored websites to mimic real investment exchanges.One survey found victims were conned for an average of $155,000 (£117,400) each.Most reported losing more than half their net worth.Those huge potential profits have driven the industrialisation of the scam industry.

Estimates of the industry’s global size now range from $70bn into the hundreds of billions – a scale that would put it on a par with the global illicit drug trade.The centres are typically run by transnational criminal networks, often originating from China, but their ground zero has been south-east Asia.By late 2024, cyber scamming operations in Mekong countries were generating an estimated $44bn (£33.4bn) a year, equivalent to about 40% of the combined formal economy.That figure is considered conservative, and on the rise.

“This is a massive growth area,” says Jason Tower, from the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime.“This has become a global illicit market only since 2021 – and we’re now talking about a $70bn-plus-per-year illicit market.If you go back to 2020, it was nowhere near that size.”In Cambodia, one company alleged by the US government to run scam compounds across the country had $15bn of cryptocurrency targeted in a Department of Justice (DOJ) seizure last month – funds equal to almost half of Cambodia’s economy.With such huge potential profits, infrastructure has rapidly been built to facilitate it.

The hubs thrive in conflict zones and along lawless and poorly regulated border areas.In Laos, officials have told local media around 400 are operating in the Golden Triangle special economic zone.Cyber Scam Monitor – a collective that monitors scamming Telegram channels, police reports, media and satellite data to identify scam compounds – has located 253 suspected sites across Cambodia.Many are enormous, and operating in public view.The scale of the compounds is itself an indication of how much the states hosting them have been compromised, experts claim.

“These are massive pieces of infrastructure, set up very publicly,You can go to borders and observe them,You can even walk into some of them,” says Tower,“The fact this is happening in a very public way shows just the extreme level of impunity – and the extent to which states are not only tolerating this, but actually, these criminal actors are becoming state embedded,”Thailand’s deputy finance minister resigned this October following allegations of links to scam operations in Cambodia, which he denies.

Chen Zhi, who was recently hit by joint UK and US sanctions for allegedly masterminding the Prince Group scam network, was an adviser to Cambodia’s prime minister.The Prince Group said it “categorically rejects” claims the company or its chairman have engaged in any unlawful activity.In Myanmar, scam centres have become a key financial flow for armed groups.In the Philippines, ex-mayor Alice Guo, who ran a massive scam centre while in office, has just been sentenced to life in prison.Across south-east Asia, scam masterminds are “operating at a very high level: they’re obtaining diplomatic credentials, they’re becoming advisers … It is massive in terms of the level of state involvement and co-optation,” Tower says.

“It’s quite unprecedented that you have an illicit market of this nature, that is causing global harm, where there’s blatant impunity, and it’s happening in this public way,”The best public interest journalism relies on first-hand accounts from people in the know,If you have something to share on this subject, you can contact us confidentially using the following methods,Secure Messaging in the Guardian appThe Guardian app has a tool to send tips about stories,Messages are end to end encrypted and concealed within the routine activity that every Guardian mobile app performs.

This prevents an observer from knowing that you are communicating with us at all, let alone what is being said.If you don't already have the Guardian app, download it (iOS/Android) and go to the menu.Select ‘Secure Messaging’.SecureDrop, instant messengers, email, telephone and postIf you can safely use the Tor network without being observed or monitored, you can send messages and documents to the Guardian via our SecureDrop platform.Finally, our guide at theguardian.

com/tips lists several ways to contact us securely, and discusses the pros and cons of each,

Skye Gyngell obituary

The pioneering chef Skye Gyngell, who has died of Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare skin cancer, aged 62, was the first Australian woman to win a Michelin star, an early supporter of the slow food movement, and a champion of charities such as StreetSmart and the Felix Project.Gyngell was a quiet radical. She came to public attention when she opened the Petersham Nurseries Café in south-west London in 2004. Until that point, she had been honing her own distinctive cooking personality that emphasised the quality of ingredients and the simplicity of their treatment and presentation. Her dishes were light, graceful and deceptively simple, but were founded on a serious understanding of how flavours and textures worked together, sometimes in surprising ways

‘Premium but not ostentatious’: the best extra virgin olive oils to gift instead of wine

This festive season, olive oil is the new bottle of wine. If booze or a scented candle used to be a fail-safe gift option for a party, retailers and food experts are reporting a surge of interest in the kitchen cupboard staple.The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more

Benjamina Ebuehi’s coffee caramel and rum choux tower Christmas showstopper – recipe

Christmas is the perfect time for something a bit more extravagant and theatrical. And a very good way to achieve this is to bring a tower of puffy choux buns to the table and pour over a jugful of boozy chocolate sauce and coffee caramel while everyone looks on in awe. To help avoid any stress on the day, most of the elements can be made ahead: the chocolate sauce and caramel can be gently reheated before pouring, while the choux shells can be baked the day before and crisped up in the oven for 10 minutes before filling.Prep 10 min Cook 1 hr 15 min Serves 10-12120ml milk 120g butter ½ tbsp sugar A pinch of salt 160g strong white flour 4-5 large eggs, beatenDemerara sugar, for sprinkling400ml double cream ½ tsp vanilla bean paste ½ tbsp icing sugarFor the coffee caramel140ml double cream 2 tsp instant coffee or espresso powder110g sugar 50g unsalted butter A big pinch of flaky sea saltFor the chocolate sauce 150g dark chocolate 1½ tbsp brown sugar 2-3 tbsp rum A pinch of saltHeat the oven to 210C (190C fan)/410F/gas 6½ and line two large baking trays with baking paper. To make the choux, put the milk, 120ml water, butter, sugar and salt in a saucepan and bring to a rolling boil

Facing burnout, she chased her dream of making pie - and built an empire: ‘Pie brings us together’

Thanksgiving may be a holiday steeped in myth and controversy – but there’s still something Americans largely agree on: there’s nothing wrong with the holiday’s traditional dessert. So says Beth Howard, expert pie maker, cookbook author, memoirist, and now documentary film-maker.The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more

Yes, there are reasons to be cynical about Thanksgiving. But there’s also turkey …

It’s easy to be cynical about Thanksgiving. The origin story that we’re all told – of a friendly exchange of food between the pilgrims and the Native Americans – is, at best, a whitewashed oversimplification. And then there’s Black Friday, an event that has hijacked one of our few non-commercialised holidays and used it as the impetus for a stressful, shameless, consumerist frenzy.The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link

Wine magnums aren’t just for Christmas – or even champagne

There are many reasons you may want to buy a magnum, and those reasons multiply and proliferate around this time of the year. Your usual night in with your partner becomes a party for six. Dinner with the family becomes an enormous pre-Christmas do, with thirsty adults and kids in the way everywhere. And watering the masses can get expensive, not to mention cumbersome.The Guardian’s journalism is independent

England abandon all-out pace attack with recall of Will Jacks for second Ashes Test in Brisbane

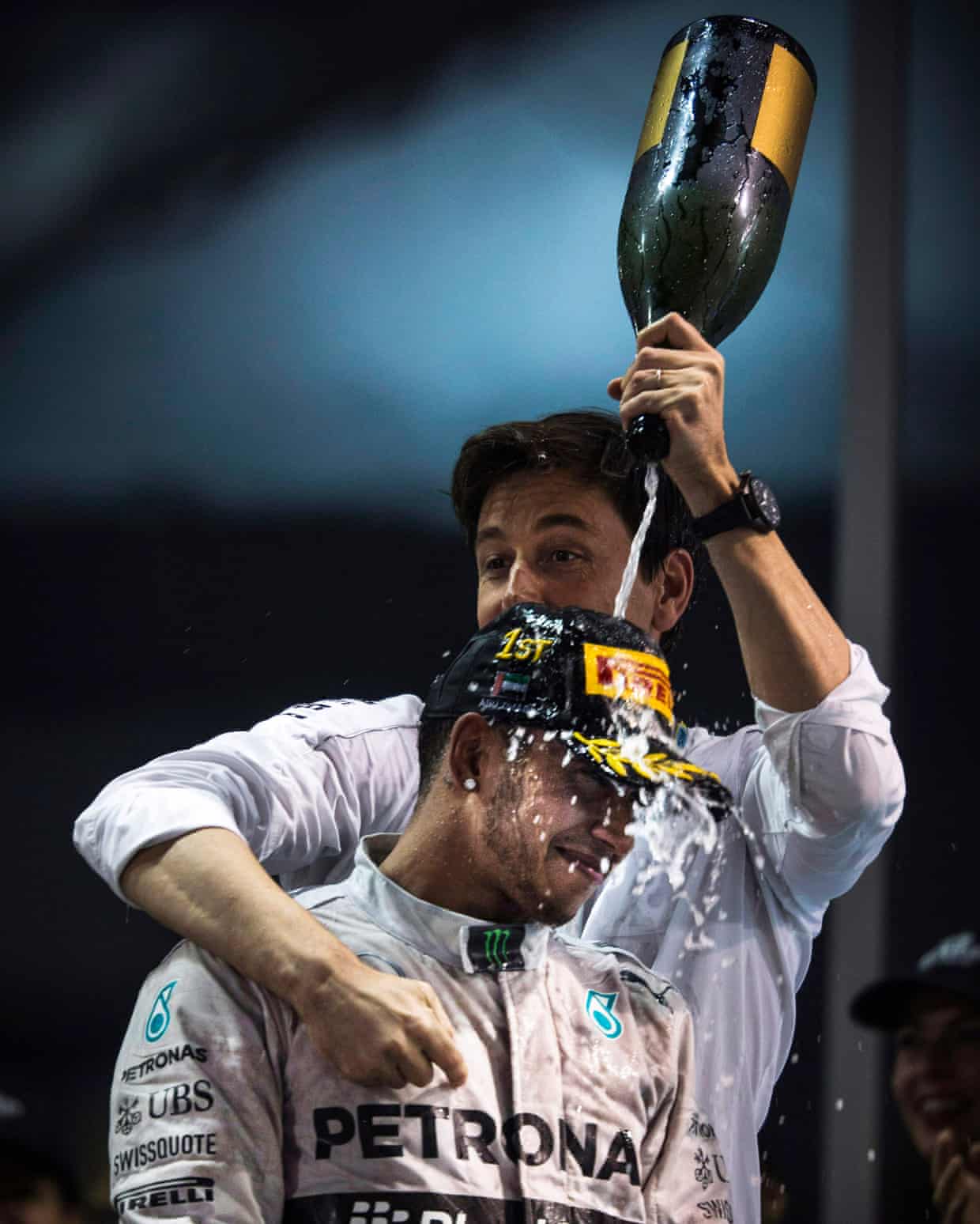

Win in Abu Dhabi and hope for carnage: how Oscar Piastri can still win the F1 world title

Max Verstappen prepared to ‘maximise everything’ in F1 season-deciding finale

Eben Etzebeth to appear at hearing after red card for alleged eye-gouging

Peter Wright obituary

Fuzzy Zoeller obituary